Tone in writing refers to a complex mix of attributes. The mood, register, attitudes and other values conveyed through details such as word choice, sentence structure and the speaker or narrator’s attitude to their subject. Read examples of tone in writing that show what creates tone in a novel or story:

What is tone in writing? Some definitions

Understanding tone in writing begins with understanding which definition we’re talking about, because there are many:

1. (Of voice): The quality of somebody’s voice, especially expressing a particular emotion.

2. (Character/atmosphere): The general character and attitude of something such as a piece of writing, or the atmosphere of an event.

3. (Of sound): The quality of a sound, especially the sound of a musical instrument or one produced by electronic equipment.

4. (Colour): A shade of a colour.

5. (Of muscles/skin): How strong and tight your muscles or skin are.

Oxford Learner Dictionaries, entry here.

For the purpose of this discussion, we’re focusing on the second definition – the general character and attitude of a piece of writing, or atmosphere of an event.

Keep in mind the other definitions, too. Each applies to the way we use tone in stories: to ‘colour’ events, such as giving a tragic scene a blue, melancholic hue. To tauten, tone and create muscly prose that lifts, for example, a thriller into tenser, terser territory.

So how do you create tone in your writing, so that a future reader might say ‘the tone of this story is pitch-perfect’?

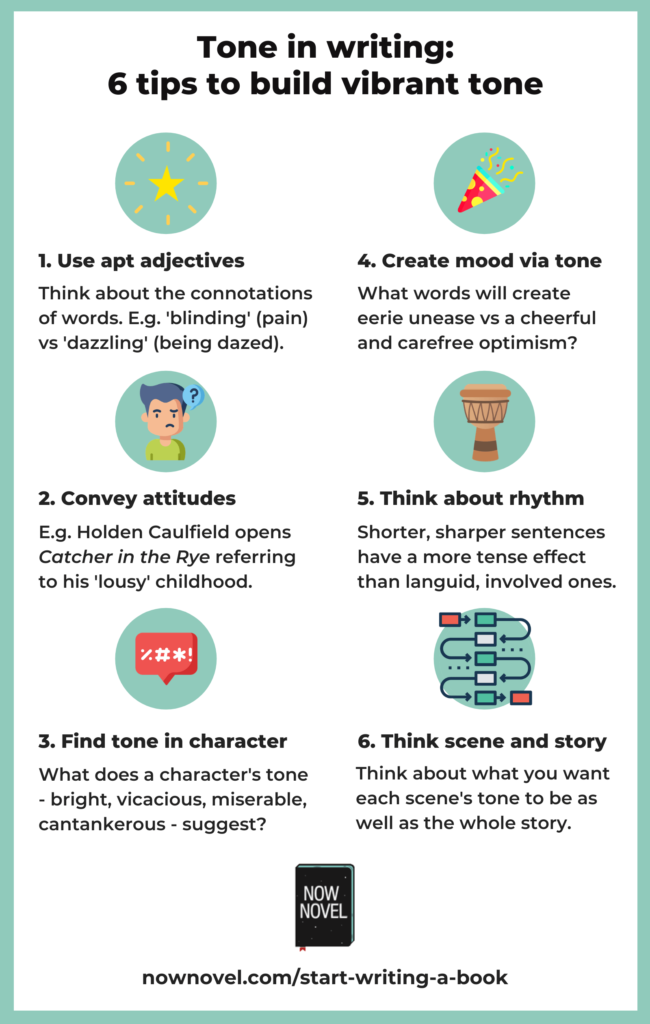

How to create tone in writing well:

- Craft tone in writing using adjectives

- Convey attitudes and feelings via word choice

- Make tone and character build one another

- Understand how tone in writing creates mood

- Pay attention to rhythm

- Think about tone per-scene and story-wide

Let’s explore creating tone further:

1. Craft tone in writing using adjectives

Adjectives are fantastic parts of speech in the descriptive specificity they allow us. Not just ‘blue’, but ‘dazzling’, ‘the palest’, or an ‘indigo-halo-around-the-mountain-at-sunset’ blue.

Adjectives create tone individually and collectively. For example, if we describe ‘dazzling’ blue, there’s a burst of vibrance and energy in that single adjective.

We could string together descriptions that contain meanings to do with light, glitter, sparkle, sheen. For example:

The dazzling blue of the bay waved a wand over the pall that had descended in the previous weeks. The blinding sheen of the boat’s railings’ made him squint as he set out on his homeward voyage.

Here, words to do with light (‘dazzling’, ‘blinding’) together create a tone of levity and vibrance, blending with the narration’s description of a darker mood being lifted by the promise of voyaging homewards.

Aspects of adjectives you can use to create tone include:

- Connotation: Compare ‘dazzling’ to ‘blinding’, for example. Describing a dress as ‘dazzling’ could imply great beauty or plenty of ‘bling’, whereas ‘blinding’ might be read with a more negative connotation of too bright, too over the top, in context

- Colour: Remember that ‘tone’ is also colour – what subtly different shades can you create using synonyms (bright, dazzling, shining, luminous) to convey the same scene?

- Sound: Sound aspects of words, what our inner ear hears while we read, contribute to tone too. For example, when we use alliteration (repeated consonants): ‘They lingered, lying above decks in languid bliss.’

2. Convey attitudes & feelings via word choice

The connotations, colour and sound of adjectives are only some of the elements of writing shaping tone.

‘Attitude’ is a key element of tone. If we say to someone, “Your tone seems very pointed right now…” what might they have said to us just before? “Put that down!” Or maybe, “What’s your problem!?”

Tone in dialogue is often easier to keep a handle on than narration, because in dialogue we know the speaker’s emotion. We have the content and context of what they say to guide us.

You can also create tone in narration by choosing words and forming sentences that convey mood, feelings and attitudes.

Example: Creating angsty tone in Catcher in the Rye

Take, for example, the icon of teenage angst Salinger created in Holden Caulfield in his novel Catcher in the Rye (1951). The words Holden uses in his opening narration convey a strong sense of his world-weary, disaffected persona:

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth. In the first place, that stuff bores me, and in the second place, my parents would have about two hemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them.

J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (1951), p. 3.

The words Salinger uses for Holden’s narration convey a disgruntled, ‘over it‘, sullen tone. A tone apt for an angsty teen. How does Salinger achieve this?

- Words with strongly negative connotations: ‘Lousy’ (describing Holden’s childhood), ‘crap’ (describing the backstory with which Charles Dickens begins David Copperfield)

- Casual register: The informal quality of phrases such as ‘kind of crap’ and ‘pretty personal’ and the exagerration of ‘about two hemorrhages apiece’ create an informal, off-the-cuff tone

- Rant-like: The effect of an angsty teenaged rant is amplified by the use of ‘one thing after another’ -type clauses strung together using the conjunction ‘and’

Salinger chooses adjectives and a style of delivery that strongly convey tone. We can feel Holden’s negativity towards the detailed exposition of Dickens’ fictional biography, or his parents’ (lack of) capacity for reasonable reaction. Explore, too, how Salinger establishes his writer’s voice.

3. Make tone and character build one another

As the example of Holden Caulfield’s narration above shows, tone in writing is closely linked to the character and attitudes of the narrating or speaking voice.

How do we know Holden is disaffected and frustrated? The tone of his voice reveals his character.

Take a simple neutral statement of fact about a sunny day:

‘The sun was shining and birdsong could be heard in the woods.’

Now imagine Tigger, the bouncy, happy-go-lucky optimist of AA Milne’s Winnie the Pooh describing the same scene:

“It was a glorious sunny day. Happy birds were calling “Hi there” and “Ta-ta for now!”

(‘Ta-ta for now!’ was one of Tigger’s catchphrases in Disney’s adaptation of Milne’s books.)

The tone of Tigger’s imagined narration here reflects his optimistic, happy-go-lucky nature.

Compare to the same scene narrated by the woeful, downtrodden donkey Eeyore:

“The sun was making the woods too hot, as usual. And the birds were at it again, making their din and having fun while nobody thought to come and visit me.”

The same essential facts are conveyed (a sunny day in the woods, birdsong in the background). Details of tone in the two voices, however, convey very different feelings and attitudes between the two characters.

4. Understand how tone in writing creates mood

‘Mood’ in writing is more difficult to define. You can think of ‘mood’ as not the feelings of the narrator but the feelings the scene is meant to elicit in the reader. Mood is the atmospheric effect of tone.

For example, Mervyn Peake’s gothic Gormenghast trilogy, about an heir named Titus Groan who inherits a crumbling, vast castle, is full of passages that create a macarbre, gothic, dark tone:

The chef of Gormenghast, balancing his body with difficulty upon a cask of wine, was addressing a group of apprentices in their striped and sodden jackets and small white caps. They clasped each other’s shoulders for their support. Their adolescent faces steaming with the heat of the adjacent ovens were quite stupefied, and when they laughed or applauded the enormity above them, it was with a crazed and sycophantic fervour.

Mervyn Peake, The Gormenghast Trilogy, p. 19.

Peake conveys the gothic mood of the scene via descriptive language suggestive of discomfort and misery (‘sodden’ jackets and ‘small’ white caps). There’s a sense of the kitchen staff’s downtrodden position in the prison-like uniforms they wear (striped) and in their ‘clasping’ each other for support.

The description of a ‘crazed’ and ‘sycophantic’ (slavishly appeasing) fervour in their applause finishes off the oppressive mood of the scene.

The tone of Mervyn Peake’s description conveys a fuller, emotive sense of the kitchen hands’ servile position relative to the chef’s greater power.

5. Pay attention to rhythm

Writing has rhythm. That sentence is short. A sequence of short sentences builds quicker pace.

The idea of the ‘rhythm’ of a piece of writing connects to the fourth definition of tone above: ‘The quality of a sound, especially the sound of a musical instrument or one produced by electronic equipment’. Short, clipped patterns of sound have a punchier effect than longer, more languid phrases.

Say, for example, you were describing a shootout after a bank heist:

The getaway had begun. Sergeant Klopper and several plain clothes gave chase. They chased the van all the way to the highway, keeping alert for a gun barrel angled back from a window. A sudden veering to the right and the crooks drove over the rumble strip. Into oncoming traffic. Klopper veered right in short succession.

The tone here is fraught and tense. Factors creating this tone include:

- Shorter, verb- and participle-fronted sentences

- Verbs, nouns and place-words suggesting risk and danger: ‘veering’, ‘alert’, ‘getaway’, ‘gun barrel’, ‘crooks’, ‘rumble’

6. Think about tone per scene and story-wide

Tone in writing is not always necessarily intentional. Sometimes a scene has a particular mood and tone because there is an underlying emotion you want to convey.

Thinking about tone scene by scene, though, and over the course of your story as a whole, with purpose, will ensure that effects such as mood and atmosphere are consistent with events and characters’ feelings and personas.

Get a detailed reader’s report; a manuscript evaluation covering pace, tone and tension, plot and characterization and much more. Take the first step to a manuscript that has publishable polish.