Dialogue in writing is tricky to master, but good dialogue carries the story. Dialogue may build pace and conflict, add tone and atmosphere, introduce and develop characters and more. Here are 5 tips to make your dialogue serve multiple useful purposes:

Making dialogue in writing drive your story:

- Use dialogue in writing for clear exposition

- Use dialogue to build tension

- Let dialogue establish tone

- Use speech to finesse character

- Make conversation quicken pace

1. Use dialogue in writing for clear exposition

Many people say not to begin a story with dialogue.

For example, Courtney Carpenter argues here at Writer’s Digest that starting a story with dialogue doesn’t give the reader context, creating confusion and the unnecessary need to backtrack.

In Carpenter’s view:

The problem with beginning a story with dialogue is that the reader knows absolutely nothing about the first character to appear in a story. For that matter, any of the characters. That means that when she encounters a line or lines of dialogue, she doesn’t have a clue who the speaker is, who she is speaking to, and in what context.

Contrary to this, an initial lack of context may add intrigue, due to mystery. Well-written dialogue often supplies plenty of context, besides.

For example, if a character fidgets with a bow-tie in the opening dialogue, we immediately know there is a degree of formality to the setting (maybe the conversation takes place at a black tie event).

In truth, dialogue at the start of a story or chapter may reveal a lot: Characters’ names and qualities, states of mind, intentions, concerns.

Dialogue in writing effective exposition: The Shining

Take, for example, the expository dialogue in Stephen King’s The Shining.

Jack Torrance is interviewing for a job at the Overlook Hotel. On page one in the first chapter we read dialogue, after the narration has described Jack thinking his interviewer an ‘officious little prick’.

King writes:

Ullman had asked a question he hadn’t caught. That was bad; Ullman was the type of man who would file such lapses away in a mental Rolodex for later consideration.

Stephen King, The Shining (1977), p. 3.

“I’m sorry?”

“I asked if your wife fully understood what you would be taking on here. And there’s your son, of course.” He glanced down at the application in front of him. “Daniel. Your wife isn’t a bit intimidated by the idea?”

“Wendy is an extraordinary woman.”

“And your son is also extraordinary?” Jack smiled, a big wide PR smile. “We like to think so, I suppose. He’s quite self-reliant for a five-year-old.”

King’s narration between the lines of dialogue, shows Jack sizing up Ullman and his character. He notes Ullman will ‘file away’ slip-ups.

Ullman’s questions about Jack’s family read as slightly invasive and full of assumption. The dialogue effectively introduces the reader to Jack’s family’s names and details such as his son’s age and self-reliance.

This is effective use of dialogue for exposition, because it supplies relevant context. It gives specific introductory information about key characters, Jack’s immediate family.

The conversation, combined with the chapter title (‘Job Interview’) supplies further context for Jack’s situation: Applying for a job that will require he and his family to relocate.

2. Use dialogue to build tension

Dialogue in writing is often an easy way to add simmering tension and conflict.

When a chapter begins “What the hell are you doing!?” we wonder who is doing what, and why the speaker is so provoked by it.

Tension in dialogue might take the form of verbal snipes a middle-aged couple, threats between hero and antagonist, or another situation where words are barbed and retorts bristle.

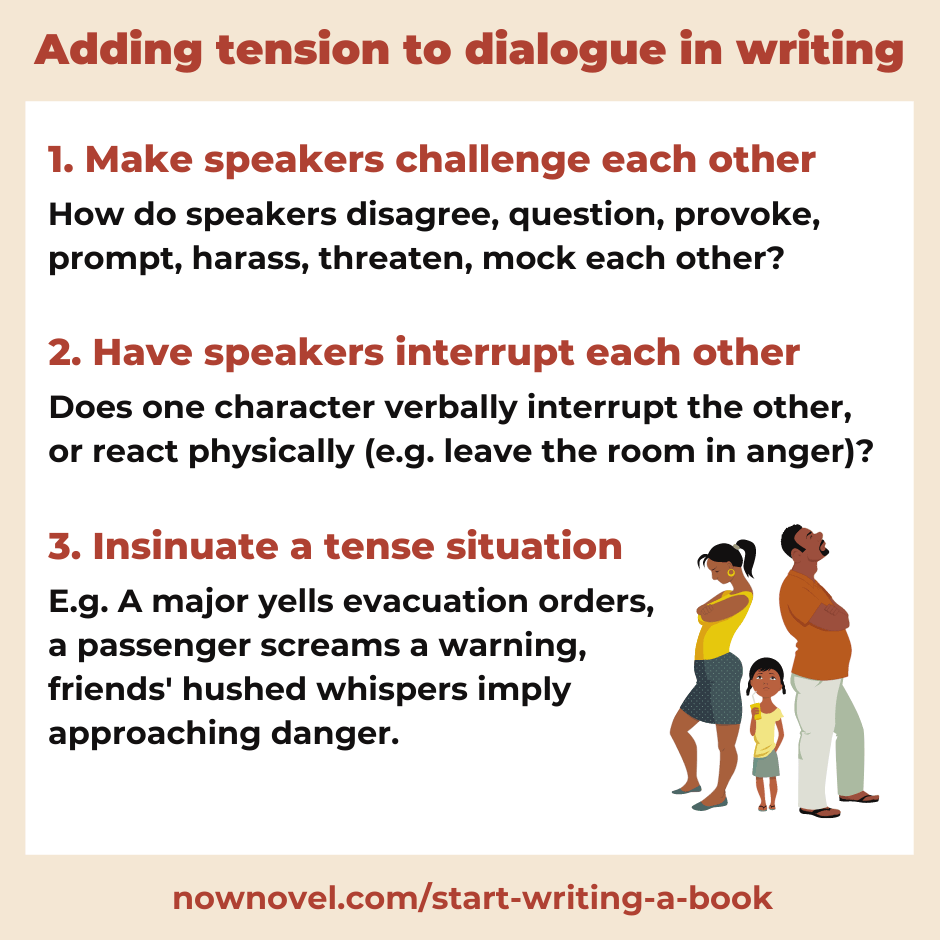

Dialogue in writing is tense when:

- Speakers contradict or challenge each other

- Speakers interrupt each other (either verbally or through action or gesture, for example flouncing out of the room mid-conversation in anger)

- Dialogue insinuates a suspenseful or tense situation (for example, when the character parodying Arnold Schwarzenneger in The Simpsons yells ‘Quick! Get to ze chopper!’)

- Dialogue infers there’s more going on than what is being said explicitly (subtext in dialogue adds another layer of ambiguity and interpretation)

Dialogue in building tension: Catcher in the Rye

J.D. Salinger has a strong ear for dialogue. When Holden Caulfield’s roommate asks him to write an English composition for him because he’s going out on a date, the conversation bristles with tension since Holden has heard he won’t be allowed back at their boarding school after the holidays because he’s failed all his other subjects:

‘I got about a hundred pages to read for History for Monday,’ [Stradlater] said. ‘How about writing a composition for me, for English? I’ll be up the creek if I don’t get the goddam thing in by Monday. The reason I ask. How ’bout it?’

J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (1951), p. 32.

It was very ironical. It really was.

‘I’m the one that’s flunking out of the goddam place, and you’re asking me to write you a goddam composition,’ I said.

‘Yeah, I know. The thing is, though, I’ll be up the creek if I don’t get it in. Be a buddy. Be a buddyroo. Okay?’

I didn’t answer him right away. Suspense is good for some bastards like Stradlater.

Salinger captures the bristling tension. He nails Holden’s awareness of (and anger about) the irony of him writing a paper for someone else when he’s failing nearly all his classes.

There’s a sense of Holden’s irritation and resistance in Salinger’s use of italics to emphasise ‘I’m’ and ‘you’re’. As Holden says, ‘suspense is good’ and here the suspense regarding whether Holden will write the paper or not builds a small pocket of tension in the scene.

3. Let dialogue establish tone

Playful banter between lovers? Snarled and spat threats between rivals? Dialogue in writing provides a quick way to establish a sense of context through tone.

Toni Morrison once said:

I never say ‘She says softly’ […] If it’s not already soft, you know, I have to leave a lot of space around it so a reader can hear that it’s soft.

Toni Morrison, in Conversations with Toni Morrison (1994), p. 136.

Dialogue in writing establishes a sense of context, of what is ‘already soft’, through:

- What someone says (content)

- When and where they say it, under what circumstances (context)

- How they say it (character)

These ‘Three Cs’ of context can be used creatively. For example, in Salinger’s example above, Holden and Stradlater’s frequent cursing (‘Goddamm’) gives a sense of context. We know these two adolescent boys are comfortable communicating with coarser language because they’re in private. It’s dialogue between peers, with a dose of bravado.

Dialogue in establishing tone: The Poisonwood Bible

Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible follows the American Price family who go on a religious mission to the Congo in central Africa.

The patriarch of the family, Nathan, is domineering and holier-than-thou. This tone is established early in the chiding and all-knowing way he speaks down to his wife and daughters:

My sisters and I were all counting on having one birthday apiece during our twelve-month mission. ‘And heaven knowns,’ our mother predicted, ‘they won’t hve Betty Crocker in the Congo.’

Barbara Kingsolver, The Poisonwood Bible (1998), p. 15.

‘Where we are headed, there will be no buyers and sellers at all,’ my father corrected. His tone implied that Mother failed to grasp our mission, and that her concern with Betty Crocker confederated her with the coin-jingling sinners who vexed Jesus till he pitched a fit and threw them out of church.

Like Toni Morrison showing words are soft using space and context, Kingsolver shows Nathan Price’s correcting, sanctimonious manner through details that provide tone. For example, Nathan Price’s pointed emphasis of the word ‘be’. This adds a rich sense of character.

4. Use speech to finesse character

The examples above all help to develop a sense of character.

In Ullman not letting any detail escape him in his interview with Jack, filing everything away in a ‘Rolodex’ in Jack’s view, we see the ‘officious’, ‘crossing every T’ type. In Holden’s casual swearing and indignation, we sense a jaded adolescent with strong feelings and opinions. There’s a sense of intelligence in his awareness of nuances such as irony.

In each instance, dialogue gives us a richer sense of each character’s personality.

Aspects of dialogue in writing that build character include:

- Subject matter – for example, a studious boarding school pupil might have a polar opposite best friend who only talks about comic books and how to scrape by in tests.

- Mannerisms – comics who do celebrity impersonations often achieve striking effects by mimicking tiny details, such as the way someone talks mostly out of the side of their mouth

- Voice – is a person’s voice deep and resonant? Thin and reedy? Unnaturally high and breathy?

Dialogue in finessing character: Love in the Time of Cholera

In Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s novel Love in the Time of Cholera, the practical man of medicine and facts, Dr Urbino, contrasts with his wife Fermina Daza who is less judgmental about fact vs fiction, self-interest vs community interest.

Consider this brief exchange. Dr. Urbino is angry that a crippled man who came to the town pretended to have led an insurrection on another island, when he was only a petty fugitive who had committed an ‘atrocious’ crime:

[…] She had supposed that her husband held Jeremiah de Saint-Amour in esteem not for what he had once been but for what he began to be after he arrived here with only his exile’s rucksack, and she could not understand why he was so distressed by the disclosure of his true identity at this late date. […]

“You don’t understand anything,” he said. “What infuriates me is not what he was or what he did, but the deception he practiced on all of us for so many years.”

His eyes began to fill with easy tears, but she pretended not to see.

“He did the right thing,” she replied. “If he had told the truth, not you or that poor woman or anybody in this town would have loved him as much as they did.”

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Love in the time of Cholera (1985), p. 32.

Marquez creates a clear sense in this dialogue of how the doctor demands ‘the truth’ and is more black and white in his thinking.

Fermina on the other hand is aware people sometimes act out of self-interest. That ‘the truth’ doesn’t guide every action equally. And in her less rigid way, she sees the relationships the man built in the town as no less real, even though they were built on an initial lie.

These small details of dialogue build a rich sense of character, and of differences between characters.

5. Make conversation quicken pace

A final benefit of using dialogue in writing is that it quickens the pace. This is a major difference (as of 2023) in dialogue writing examples by human authors vs AI generation. We have a much more finely attuned sense of the rhythms of speech.

Often, a few simple lines of dialogue achieve what it would have taken pages of complex narration to communicate.

For example, let’s compare two descriptions of art thieves at work:

Example One

Here, we narrate context:

The men had pored over plans for month, scouring every entrance and exit. Learning which camera was where, which window or door measured what dimensions. Now they were ready to move. They had cleared every hurdle and were now slinking out of the building, carrying the large oil by Van Apel.

Example Two

Compare the same information as above conveyed with context bundled with dialogue:

“Glad we studied those plans so w-“

“Keep your voice down!” the man’s accomplice cast an anxious glance around him for the gallery’s guard, double-checking there were no cameras in sight. It was nighttime and they’d timed the operation well, but something could still go wrong.

“Why did we choose this damned Van Apel oil,” his friend whispered, grimacing. “Will it even fit in the van?”

Dialogue pulls us into a scene, the speaking voice signalling to us to pay attention. It enlivens the pace, by making the setup less apparent, bundling it with voice, character (the cautious man contrasting with his less cautious accomplice).

Next, read our complete guide to dialogue writing. Also read our points to consider when writing dialogue.

Need help with your dialogue? Join How to Write Dialogue for workbooks, exercises and feedback, or take our free 5-day email course.