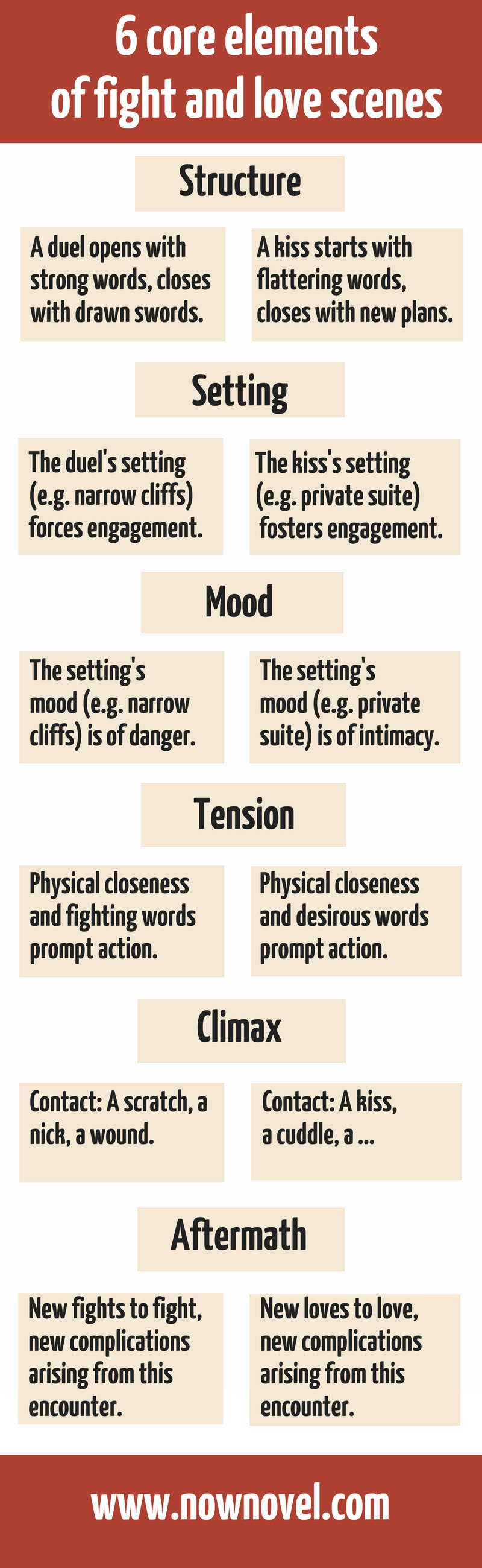

Writing romantic scenes between lovers and writing fight scenes (between lovers or heroes and villains) might sound miles apart. Yet both share common important elements:

1. Structure (shape, purpose, clarity and direction)

There are four things great scenes of all types (not only romance and conflict scenes) require.

Firstly, strong scenes have structure; shape. We sense when things are building to the mid-point or drawing to a close. We discover what place and scenario the scene is concerned with and things play out from there.

Secondly, great scenes have purpose. Besides entertaining us, they illustrate an important detail of plot (for example the reason for the main character’s sour or sunny disposition).

Thirdly, great scenes have clarity. A fight scene is impossible to follow when you can’t tell who is insulting or attacking whom.

Finally, the best story scenes have clear direction. We can sense where they are headed due to characters’ behaviour and thoughts, due to scene setting (and changes in setting) and other signs of progress towards characters’ goals.

(You can read concise information on writing great scenes, including examples of effective scene opening and development, when you download our free guide to scene structure).

Read elements worth including in a structured romantic scene or character conflict:

2. A setting that allows the encounter to develop

In a steamy romance scene, the setting is typically somewhere private, where characters who are lovers (or not yet lovers) can get intimate. For example, special FBI agents become more than colleagues when they have to share a hotel room. Adventuring fantasy duos kindle more than a fire when they need to keep warm overnight in a cave.

Similarly, in the best fight scenes, the setting actively contributes to the encounter possibilities of the scene. In an abandoned warehouse law enforcement might have a hard time finding their way around. This creates time and space for a major scene of conflict to play out.

Settings in romantic scenes and fight scenes alike force characters to face the inevitable, be it a kiss or a sword fight.

An example: The train to Hogwarts in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (1999) is an excellent setting for a confrontation between Harry and one of the chilling wraith-like creatures sent to guard the school against alleged murderer Sirius Black.

Given these creatures’ stationing at the school, it is inevitable there will be an encounter between them and Harry. Yet the train to school stops between stations, and the usually safe space transforms into the stage for an eerie, unsettling encounter, as the Dementors board in search of Sirius.

The fact that one almost attacks Harry foreshadows further conflicts between students and Dementors. It also creates a sense, from the outset, that no setting or space in the novel is safe from attack, contributing to the novel’s darker, more menacing tone.

The example above is a good reminder that a setting can be either the probable or improbable location for a fight (or romantic encounter). Ghoulish creatures might attack on the shores of a dark, deserted lake at nightfall. Yet when they do in a daytime setting assumed secure, the effect is often stark. There’s good contrast. Similarly, two lovers might grow more intimate and kiss in a secluded, private space, but romance can also strike by surprise in unlikely places.

Whether your setting is typical for a fight or romantic scene or not, think about what it contributes to your scene. For example, in the Harry Potter example above, because the near-attack occurs on a train in the middle of nowhere, Harry can’t simply leap off and dash to safety. This sense of confinement ups the tension. Setting in fight and romantic scenes alike should foster the conditions for unavoidable contact.

3. Scene-supporting mood

Mood is a crucial element of both love scenes and fight scenes. Factors that contribute to the mood of a scene include:

- Setting and scene description: Tone and language help convey mood, whether a place is creepy or bright, claustrophobic or expansive

- Character psychology: The frame of mind of your focal or narrating characters shapes mood too. For example, a highly strung, anxious potential lover might make a usually-romantic setting appear dangerous, full of opportunities for embarrassment and awkwardness. Maybe there are stairs to fall down, vases to knock over.

Mood should be relevant to the primary events of a scene. If the mood of your scene is dull and passionless, it could seem odd if characters suddenly start tearing each other’s clothes off. Think of small, significant details that build a romantic (or, in a fight scene, combative) mood.

In both scene types, these include:

- Character exchanges (looks, words)

- Actions (e.g. lighting candles or dimming lights (romance); cleaning/loading a gun; fastening a bulletproof vest (fighting)

- Scene description (e.g. a looming building with no windows and one exit (fighting); a softly-lit room with a hissing and popping fire (romance)

Well-crafted mood adds to tenderness or animosity, filling out your scene with the detail that makes characters’ actions seem even more inevitable.

4. Tension: the building block of romance and conflict

A romantic scene and a fight scene have something further in common: Both trade in raw emotion. Characters’ desires and goals and how they align or compete lead to romance or conflict. Both paths are full of possible tension.

In a romantic scene, you can express tension between characters verbally and/or physically. Characters’ conversation, for example, might be overly polite, with the strained silence around what’s said speaking volumes. This sort of strained conversation is effective for suggesting that there is something being held back (a confession of desire or love, or anger). It’s a subtle form of tension that often features in period novels (as in the example below) that explore the difficulties of courtship.

How to build romantic tension in a scene

To build romantic tension in a scene:

- Use physical proximity: The closer characters get, the more likely physical contact (a kiss, cuddle or more) becomes

- Use dialogue: Perhaps a character hints at their desire for the other, or talks hypothetically. They might initiate a conversation about turn-ons and turn-offs or other romance-related subjects

Consider this example from George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871). Eliot builds tension between two characters, Rosamund Vincy and the idealistic doctor Tertius Lydgate (they eventually marry with unhappy outcomes):

Miss Vincy was alone, and blushed so deeply when Lydgate came in that he felt a corresponding embarrassment, and instead of any playfulness, he began at once to speak of his reason for calling, and to beg her, almost formally, to deliver the message to her father. Rosamond who at the first moment felt as if her happiness were returning, was keenly hurt by Lydgate’s manner; her blush had departed, and she assented coldly, without adding an unnecessary word, some trivial chain-work which she had in her hands enabling her to avoid looking at Lydgate higher than his chin.

The tension of desire and expectation, and the awkwardness of romantic feelings held back, together create a sense of suspense. Both characters appear to avoid direct connection.

How to build tension leading to conflict in a fight scene

The factors contributing to tension and eventual contact in a fight scene are similar to those of a romantic scene. Physical proximity between hero and villain (or two warring lovers) is naturally necessary for things to escalate.

Dialogue is also important, too. It is through dialogue that one opponent might taunt or insult the other enough to prompt an exchange of blows.

Consider this example, the classic sword duelling scene between Inigo and the man in black in William Goldman’s much-loved fantasy romance novel, The Princess Bride (1973):

They were moving parallel to the cliffs now, and the trees were behind them, mostly. The man in black was slowly being forced toward a group of large boulders, for Inigo was anxious to see how well he moved when quarters were close, when you could not thrust or parry with total freedom. He continued to force, and then the boulders were surrounding them. Inigo suddenly threw his body against a nearby rock, rebounded off it with stunning force, lunging with incredible speed.

‘First blood was his.’

Throughout the conflict, the characters’ proximity increases until they’re surrounded by boulders. Goldman also increases the scene’s tension succinctly with the words ‘first blood was his’, because the words imply it is the first injury of more to come.

Later in the fight, Goldman also uses dialogue to build tension further:

“You are most excellent,” he said. His rear foot was at the cliff edge. He could retreat no more.

“Thank you,” the man in black replied. “I have worked very hard to become so.”

“You are better than I am,” Inigo admitted.

“So it seems. But if that is true, then why are you smiling?”

“Because,” Inigo answered, “I know something you don’t know.”

“And what is that?” asked the man in black.

“I’m not left-handed,” Inigo replied, and with those words, he all but threw the six-fingered sword into his right hand, and the tide of battle turned.

Goldman builds tension to a climax with physical sparring and description, then uses dialogue for a dramatic reversal.

A similar effect could be achieved in a romance scene by making two characters get closer physically until one speaks, admitting desire (or, for a complication, a devastating bombshell).

5. Climactic moments (e.g. physical contact)

After all the tension building, the groundwork preparing a fight or embrace, the scene comes to a head. Some scenes may instead use anti-climax (also called bathos) to reduce tension or defer a dramatic encounter to a later stage (effectively sustaining primary unresolved tensions longer). For example, characters burst into the fifth floor room where they think a villain is hiding, only to see a small, open window with a makeshift rope hanging down the side of the building (indicating a getaway).

Exceptions aside, typical romantic scenes and fight scenes build to engagement between characters. So how do you create compelling climactic moments? Some suggestions:

- Shift action to increasingly constrained locations: In the example from The Princess Bride above, the movement from a sparsely wooded area to a claustrophobic space between boulders, then the cliff’s edge, creates variation in tension and constraint

- Up the stakes: In the sword fight above, the man in black gets Inigo to a precarious position, upping the need for clever thinking on Inigo’s part.

- Vary action with turning-points signalled by words and gestures: Inigo switching to his dominant hand is paired with dialogue that makes it clear we’re reaching a new peak of intensity and action

6. An aftermath

Every conflict and every romantic entanglement has an aftermath of some kind. In a romance, for example, the co-workers who hook up after a wild work celebration still have to file into a team meeting straight-faced on Monday. While we usually mean ‘aftermath’ in the sense of fallout, of negative results, a key conflict or romantic encounter may also be a positive turning point for your characters.

Within the aftermath of a conflict or romantic encounter lie the seeds for further character motivations and choices. For example, in Eliot’s Middlemarch, the encounters between Rosamund and Tertius lead to eventual marriage, but the aftermath sees Tertius give up his ideals due to Rosamund’s controlling, status-obsessed nature. That’s the aftermath of the encounter. When you plan or draft a romantic scene or fight scene, ask:

- How does this scene prepare or foreshadow what comes next?

- What useful additional complications could it raise? For example, characters who, in the heat of the moment, have sex without protection will likely face the worries of possible unplanned pregnancy or STD contraction. Complications such as these show the consequences of characters’ choices and the new choices and dilemmas

the story will make them confront

Do you need constructive input on a scene of romance or contact? Join Now Novel and get helpful feedback from an online writing group or personal writing coach.

2 replies on “Writing romantic scenes and fight scenes: 6 parallels”

This brings in a new perspective for my action and romance scenes. I definitely will keep this in mind. I never thought that there would be so many parallels between lovers and enemies. Very interesting. I can’t wait to put this into practice.

Hi Marissa, thanks for your feedback and for reading. Glad to hear you’re motivated to write. Have a good weekend.