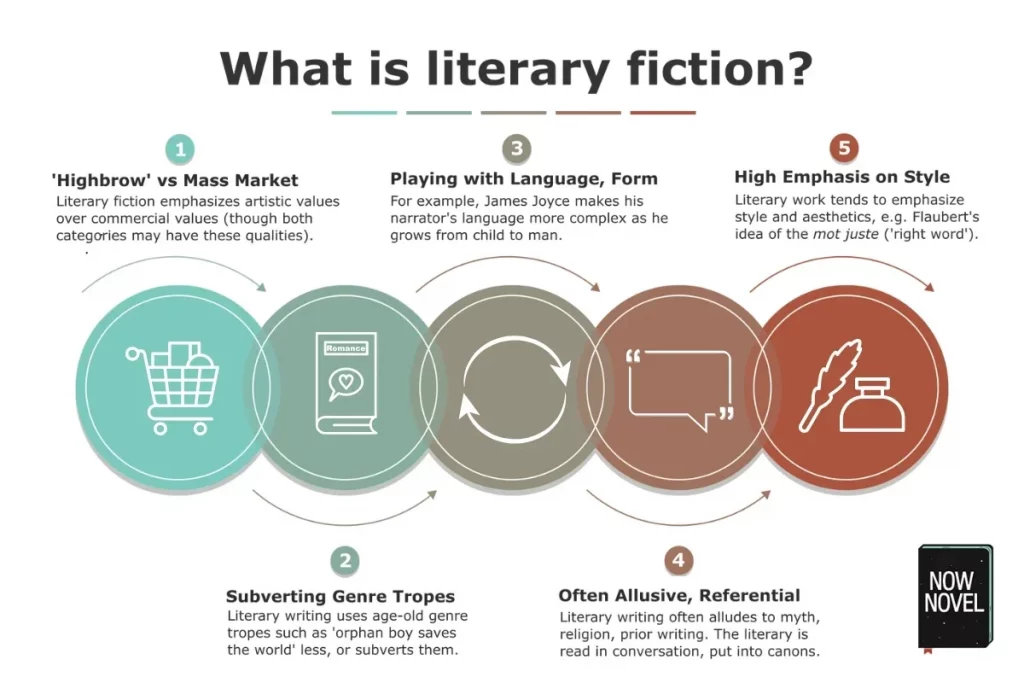

What is literary fiction? Literary fiction explores subtleties and complexities of language, theme and symbolism. It often tends to be character-driven rather than plot driven. Read a definition plus tips on how to develop literary writing style.

How do you define literary fiction?

If you read the definition from Oxford Languages and the Cambridge Dictionary, combined with other definitions from around the web, it becomes clear that literary fiction is:

- valued highly for its quality of form, endurance and playful use of language

- writing placed into the category ‘literature’ (books culturally accepted as ‘literary’ because they have common features such as elevated writing style or dense allusion)

Examples of literary fiction include the modernist author Virginia Woolf’s book To the Lighthouse and the novels of Nobel-winning authors such as Toni Morrison and J.M. Coetzee.

Common features of literary fiction

Demanding subject matter, themes, or interpretive framework

Often, literary fiction is more ‘demanding’ than genre fiction. Like genre fiction, (or as it’s sometimes known, commercial fiction), it may use tropes such as the Hero’s Journey, yet may depart more from expected conventions, too.

This is one reason why many describe literary fiction as cerebral or ‘difficult’. It tends to require the reader to be more active in the act of making meaning and interpreting. It doesn’t always hand a decisive, singular interpretation to the reader, wrapped in a neat bow.

Literary fiction writers sometimes have open-ended storylines, with the reader being left to decide what the ending might or could be. It often, when written in the realist tradition, has a quality of real life, of the story continuing beyond the page, as it were. It often offers a deep dive into the nitty gritty of human experiences. This type of story is very often focused on the journey, on what is discovered, than on reaching a set end point. For example in a murder story, it is important that the murderer be discovered, readers of such fiction will expect it. However, in a literary whodunnit, the murderer may never be discovered. The writer may be exploring themes such as guilt, or how the past can wound a protagonist, or philosophical questions about the meaning of life.

Here’s an interesting and useful definition from Nathan Bransford: ‘In commercial fiction the plot tends to happen above the surface and in literary fiction the plot tends to happen beneath the surface, and in literary fiction the prose has a unique, distinctive style.’

A too-easy definition of literary and genre fiction is that genre fiction is more dependent and focused on plot, while literary fiction is based solely on character. While this is true of some novels in each camp, every story should tell a story, i.e. something must have happen. There has to be a sense that the character(s) have discovered something about themselves, or have been changed by an experience in a literary fiction novel, for example.

Emphasis on context and milieu (in reception)

The themes and subtexts or references of the text (often serious rather than comedic) in literary fiction are often important.

Writing happens in a context, after all. It happens in place and time. A story’s social and historical context (aspects of reading that change over time) shapes (and shifts) how readers approach it.

Part of this is due to the way literary texts are given as set works and studied in educational contexts. Critical thinking requires learners to read more broadly, compare texts, situate them in their contexts (or create interesting new conversations between them).

A story’s literary status is not static

Many books classified literary were written in past centuries. The so-called classics.

Societal beliefs and values change. Vocabularies do, too. Charles Dickens, now found on ‘Classics’ shelves, was the Stephen King of his Victorian times. The way he serialized popular stories such as The Pickwick Papers (1836) predates Kindle Vella.

Literary vs popular fiction: Blurring the line

Before we discuss ways to develop your literary style, we’ll briefly examine the ‘literature vs genre’ debate, and the idea of genre snobbery.

Literary is a bookstore category, not a genre

A lot has been written debating the merits of literary fiction versus genre fiction (genres such as fantasy, romance, crime, thriller).

Elizabeth Edmonson, writing for The Guardian, for example, argues that Jane Austen wasn’t writing ‘literature’ and that posterity made that decision for her. In some respects it’s true that ‘literary fiction is just clever marketing’, as her article’s title suggests.

But what are some useful differences?

Literary fiction may combine genres or create its own

Many novels classified as literary are simply tough to categorize. Experimentation, subverting tropes or narrative conventions, might weaken argument a story fits this or that genre, for example.

Sui generis (Latin for ‘of its own kind’) stories might mix fictive elements with non-fiction.

Genre fiction tends to require of writers that you know your genre and deliver on its promises. For example, the reader knows they’ll find the meet cute and happily ever after in feel-good romance. In a mystery novel the reader knows the mystery will be solved.

Now Novel writing coach Romy Sommer shares more on knowing your genre in the writing webinar extract below:

Literary writers have explored hybrid genre often. Several of Margaret Atwood’s books explore science fiction or speculative themes, as did Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go. Doris Lessing started out as a literary writing, and then also published science fiction, as well as literary novels.

Graham Greene famously alternated between writing literary fiction and genre thrillers while the Scottish literary writer Iain Banks published science fiction novels as Iain M. Banks.

Other literary books mash up multiple genres (David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, for example, which mixes historical, detective, dystopian and sci-fi elements).

Get a literary critique partner

Work one-on-one with a writing coach who understands literary style.

LEARN MOREGenre fiction has many of literary fiction’s hallmarks

Although some may say literary fiction is ‘art’ while genre fiction is ‘mass market’, can one say this about the epic historical quality of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings cycle?

Many essays and even whole books argue that Tolkien deserves ‘serious’ study in literary and critical establishments.

Some genre fiction also concerns itself with elements such as language and is not necessarily plot-driven (a common but false distinction used to separate genre from the literary – plot-driven equals genre, while character-driven equals literary).

Examples of writers who write or wrote genre fiction but who are literary in the breadth and depth of their work include Ursula K. Le Guin, John le Carré and Neil Gaiman.

Literary fiction and the genre snob debate

Some argue that literary fiction goes hand in hand with snobbery or elitism. But literary novelists may come from any number of backgrounds.

Whether or not you see it as rarified, complex or overwrought, literary fiction has a great deal to offer. If you usually write genre fiction, reading literary fiction can show you ways to use language and form playfully – though not reinventing the wheel entirely does ensure the accessibility that helps genre fiction sell.

Whether your focus is primarily genre or literary fiction, here are some of the ways that you can develop your own literary style:

How to develop literary style in writing:

- Avoid or subvert genre clichés

- Read literary writers

- Copy out passages from literary works you like

- Play with form and narrative conventions

- Go deeper with allusion and intertext

1. Avoid or subvert genre clichés

In some genre fiction, heroines are always beautiful, heroes always brave. The detective always solves the crime. People live happily ever after, and good prevails over evil. Bad guys are bad through and through.

There is nothing wrong with these clichés (or rather, tropes – story elements that recur and are recycled). Authors repeat tropes because:

- They are familiar and recognizable and thus comforting – we know what we’re getting in a James Bond movie

- Readers of specific genres tend to expect them

- They often serve important story elements such as plot development, or characters’ goals, motivations and conflict

Professional editing

Let our editors polish your manuscript. From language subtleties to structural depth, we ensure your literary fiction meets the highest standards.

Get a quote

How to make stories literary – undercut genre tropes

Genre fiction often gives us tropes such as ‘innocent orphan boy must save the world’ (Star Wars, Harry Potter). Literary fiction often turns these commonly recycled ideas upside down.

What happens if a crime is never solved? David Lynch famously ended Twin Peaks (a very postmodern – some would say ‘difficult’ – TV show often requiring the viewer to draw their own conclusions) on a detective becoming a possible antagonist. The story thus opens out into disturbing possibility rather than providing the comfort of closure.

What if two people move mountains to be together and then discover they don’t actually like one another very much? In literary fiction this might be the premise for a tragic or comedic story.

The bleak, violent, morally ambiguous world of George R.R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire is a far cry from high fantasy fiction in which good prevails. Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley crime novels are not about a cranky detective catching a criminal. Instead, they’re narrated by a sociopath.

Think of ways you could subvert or undercut what is expected of genre elements in your story. This is a common literary device, including parody (which sends up or pokes fun at typical genre ploys).

2. Read literary writers

You need to read the kind of fiction you want to write. Answering the question ‘what is literary fiction?’ is easier the more you read.

Make an effort to read some of the classic writers (such as Toni Morrison, Virginia Woolf, Chinua Achebe and William Faulkner, for example) as well as contemporary writers.

Magazines such as The New Yorker, The Paris Review and Granta publish short fiction by the top literary writers of today.

Prizes such as the Booker and the Nobel Prize for Literature can point you towards critically acclaimed literary novels, too.

As you read, notice the many different types of literary writers and how writers like Gabriel Garcia Marquez or Helen Oyeyemi experiment with genre or the fantastical. On the other hand, writers such as Alice Munro and Jonathan Franzen work in a more realist storytelling – yet still literary – vein.

Reading literary fiction avidly will help you understand its conventions well. When you try to write it, start by imitating authors you love because this will help you develop your style:

3. Copy out passages from literary works you like

Copy out sentences by famous literary authors often. This is how Bach (considered one of the greatest masters of western classical music) learned musical composition.

In addition to copying passages word for word from the writers you admire, you might also try to write some passages of your own or even an entire story mimicking an author’s style.

John Banville wrote Mrs. Osmond as a kind of literary-pastiche-meets-sequel after Henry James’ The Portrait of a Lady.

Copying writers you love helps because you pay closer attention to the mechanics. You peel back the skin to see the bones that knit together an author’s specific writing style and voice. This helps you assimilate the elements you like, and filter them through your own voice.

No monthly fees!

Ensure your literary fiction journey never ends with Lifetime access. Join a community of writers and continue to grow and refine your craft.

GET ACCESS4. Play with form and narrative conventions

One thing you’ll notice as you read literary fiction is how freely literary writers depart from narrative convention.

This is nothing new; many consider the 18th century novel Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne an early forerunner of 20th century postmodern playfulness.

In the early 20th century, modernist writers like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf play with language and modify traditional narrative structures. Decades later, David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest told much of its story via footnotes. In literary writing, we don’t have to reproduce traditional ideas about storytelling or ‘given’ forms.

In Latin and Central American writers introduction magical realism into some of their literary fiction. Damon Galgut’s Booker winner The Promise is a literary novel that plays with form: it’s set over four funerals through the years, and point of view often changes between characters, sometimes within the same sentence.

Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House plays around a lot with the genre of autobiography/memoir. JM Coetzee’s Dusklands is another prototypical example of telling the same story twice in different ways in the same book.

Meanwhile Anthony Horowitz’s Magpie Murders is a mystery novel by Anthony Horowitz and the first novel in the Susan Ryeland series. The story focuses on the murder of a mystery author and uses a story within a story format.

Genre has its experimental writers as well such as science fiction Samuel Delany. Mark Z. Danielewski, while not necessarily a horror writer, wrote a haunted house novel, The House of Leaves, that upends both narrative and typographical expectations.

5. Go deeper with allusion and intertexts

Intertext – literally ‘between text’ – is a literary theory term coined by theorist Julia Kristeva. It refers to the way writing exists in conversation with other writing.

A hallmark of literary fiction is that it often draws on other writing. One way it does this is through allusion (for example, the way Aslan being resurrected in C.S. Lewis’ Narnia series calls to mind Jesus Christ).

A character hesitating or looking back and losing everything by doing so would immediately call to mind (for those familiar with it) the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice.

Some literary texts literally rewrite or retell prior stories, from different or novel vantage points. As an example, Jean Rhys in Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) tells the story of Bertha, a secondary character in Bronté’s classic Jane Eyre (1847), from a more feminist perspective. Also have a look at how Jane Eyre fits into the Hero’s Journey from a feminist point of view. Thus although it’s a literary novel, it uses a genre trope, that of the Hero(oine)s Journey.

How can you hide easter eggs or allusions for the astute or well-read reader to discover? Or how how might you ‘write back’ to a previous story, questioning some of its blind spots, the failings or follies of its times? These are literary questions.

For a discussion on how to develop your writer’s voice, in any genre, read this guide.

If you want to start and finish writing a literary novel, get writing feedback and help developing your book on Now Novel.

16 replies on “What is literary fiction? How to develop a literary voice”

Overly obsessed with patting the bottom of genre fiction.

This is a great phrase (though I’m not sure who is overly obsessed with patting bottoms here) – as long as it’s consensual! 🙂 Thanks for reading.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this essay on literary fiction! Such great points and no, I don’t think it is condescending to genre writers at all.

I’m writing my first Literary Fiction novel after attending the Iowa Writers Workshop 26 years ago.

I read/listen to mostly thriller And detective fiction. But I read/listen to James Lee Burke, Greg Iles, and other authors who really like to use language in form and meaning. I find there are many great works in genre fiction that cross the lines.

Great piece! I’m bookmarking this!

Hi Iowashorts, thank you for sharing that! It’s true, many works do blur the lines between the literary and the popular. Thank you for reading our blog and sharing your thoughts, and good luck with your novel.

This was very informative. Thank you for writing this. I want to write children’s books. Does this information apply to that genre and if it does, could you recommend some examples?

Hi Angela, it’s a pleasure, I’m glad you found this helpful. I would say it does not entirely, as literary fiction is quite far from children’s books in terms of style, format, tone and reading level typically. Children’s author Alan Durant has a good article on writing for younger readers for Penguin UK here.

What about literary faction?

What about it, DF? Please share your thoughts.

Fiction, fiction, fiction … why are so many historical and in particular espionage novels thus? It is a real shame more historical and espionage thrillers aren’t truly fact based. Courtesy of being fictional the readers’ experience is narrowed and the extra dimensions available from reading fact based books are lost. Factual novels enable the reader to research more about what’s in the novel in press cuttings, history books etc and such research can be as rewarding and compelling as reading an enthralling novel. Furthermore, if even just marginally autobiographical, the author has the opportunity to convey the protagonist’s genuine hopes and fears as opposed to hypothetical drivel about say what it feels like to avoid capture. A good example of such a “real” espionage thriller is Beyond Enkription, the first spy novel in The Burlington Files series by Bill Fairclough. Its protagonist was of course a real as opposed to a celluloid spy and has even been likened to a “posh and sophisticated Harry Palmer”. The first novel in the series is indisputably noir, maybe even a tad Deightonesque. If anyone ever makes a film based on Beyond Enkription they’ll only have themselves to blame if it doesn’t go down in history as a classic espionage thriller.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts about fiction vs historical/factual books, Daniel. A very interesting read.

One thing it made me think of is how theorists of historical writing have posited that history is also written with agendas, points of view, and other imaginative or ‘invention-oriented’ (for want of a better word) principles, so that history texts presented as non-fiction do not necessarily give us ‘non-diluted’ truths (or avoid hypothetical drivel!). In some instances, history has been written by technologized victors, for example, while the side of the story in oral cultures goes untold – at least in books.

So I agree with some of what you say, but I also like how reading fiction can help a person to arrive at a sense of ‘truth and lie in an extra-moral sense’ (to borrow a phrase from Nietzsche), through the cracked mirror of invention.

to the question of why aren’t more historical/espionage books fact based? well other than the huge question of whose version of events to base the story on, I prefer to write made up worlds that are *very* similar to real places and events because of the zeitgeist, i.e. the fear of being torn down not on the merit of the story but on the ‘authenticity’ of the voice and location.

Hi Jen, thank you for sharing your perspective and contributing to the discussion. That’s true about factual writing, that it becomes a question of perspective and how one deals with multiple versions of events or possibly contradictory sources. This is one of the reasons why some authors prefer to blend factual and fictive elements (and give a caveat that a story is partially factual).

I remember a history textbook from my schooling days that had a single, ‘grand narrative’, but then used text boxes with micro histories throughout (individual people’s stories). This worked well as you got a sense of the broad sweep of history, plus a chorus-like sense of multiple perspectives and the different experiences across class and ethnicity. Alternating viewpoints would be one way to incorporate different sources like this in a narrative-only format.

Following the advice to read what you want to write, can you recommend any contemporary literary fiction written in third-person omniscient POV? I’m new and having difficulty finding that combination with my poor search abilities.

Hi James, thank you for your question. What genre are you writing? Third-person omniscient isn’t nearly as popular today as it was in previous eras as it’s fallen out of favor to a large extent as more writers adopt either limited third person, first person or multi-POV fixed viewpoints (for example, a novel with three first-person narrators whose viewpoints alternate). A contemporary example that comes to mind (though not that recent) is Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief which is narrated by Death personified. What confuses matters is I’ve seen many lists proclaiming books to be third-person omniscient when they are actually multi-viewpoint third person. For it to be omniscient, a single character or non-involved narrator must be able to know what is happening to (or has happened to) multiple characters; changing viewpoint alone does not make the POV omniscient.

Hello, James! I am newish, too. I’m not too keen on the modern trend of writing in the first person, either. Two years ago, when I began my Mediocre American Novel, I thought I was writing in third-person omniscient. I soon realized that I was using third-person limited. The POV sometimes changed rapidly, but the reader never received information hidden from the characters.

Thank you for joining the conversation, Kathy! I love ‘Mediocre American Novel’, haha. I’m guessing it’s a riposte to the idea of the ‘Great American Novel’.