Third person limited point of view (or POV) is one of the most common POVs in modern fiction. What is third person limited? How can you use it effectively? Read a Ursula K. Le Guin’s definition, plus tips and examples:

What is third person limited POV?

Third person narration is narration using pronouns such as he, she, newer gender-neutral third person singular pronouns, or they. In this type of narration, the narrator is usually ‘a non-participating observer of the represented events’ (Oxford Reference). In other words, the narrator exists observes and reports the main events of the story.

Third person limited differs from omniscient third person because the narrator is an active participant. Although the pronouns may be the same as in omniscient POV, the narrator only knows what a single person or group (the viewpoint narrator or current narrator) knows. Or, as Ursula K. Le Guin puts it in her writing guide Steering the Craft (1998), in limited third person:

Only what the viewpoint character knows, feels, perceives, thinks, guesses, hopes, remembers, etc., can be told. The reader can infer what other people feel and think only from what the viewpoint character observes.’

[Novel coaching editor and author Romy Sommer shares additional tips on POV in our monthly webinar series – follow Now Novel on YouTube for helpful extracts and tips.]

So how do you use third person limited POV well?

How to use third person limited POV:

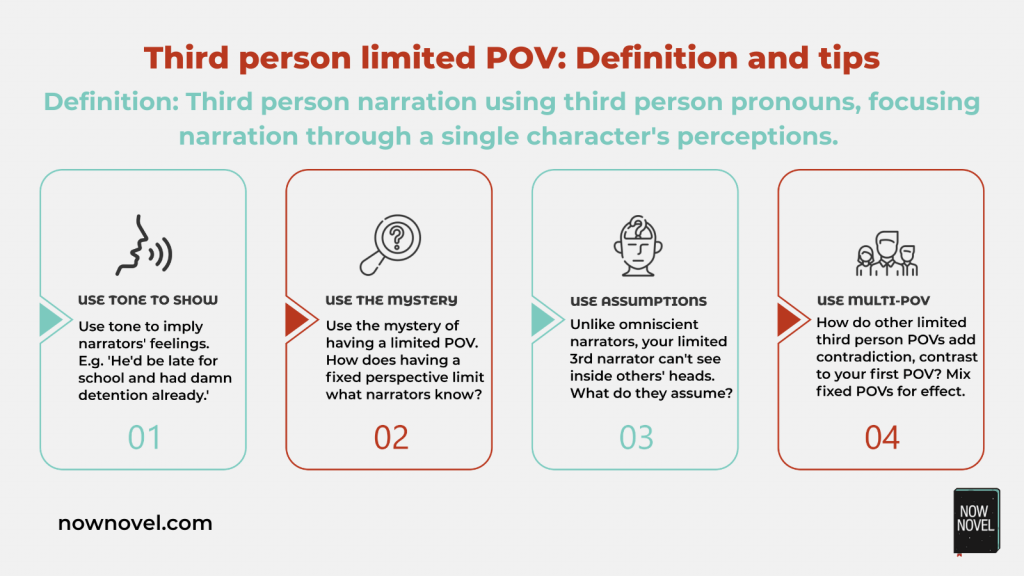

- Use tone in limited third person narration to show feelings

- Show the mystery of a limited point of view

- Show characters’ mistaken assumptions

- Contrast limited viewpoints to show contrasting experiences

1. Use tone in limited third person narration to show feelings

Third person limited POV works well for showing how others’ actions impact your viewpoint character. Because you can only share what your viewpoint character knows or guesses, other characters’ actions keep all of their mystery.

In limited third person, our guesses regarding what other characters’ private thoughts and motivations are become only as good as the narrating character’s ability to observe, describe and interpret.

Example of effective tone in third person limited POV

For example, J.K. Rowling uses limited third person narration in her Harry Potter series. In Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (1998), she shows how habitual mistreatment by his aunt and uncle give Harry low expectations of occasions we’d expect to be happy:

The Dursleys hadn’t even remembered that today happened to be Harry’s twelfth birthday. Of course, his hopes hadn’t been high; they’d never given him a real present, let alone a cake – but to ignore it completely…

J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (1998), p. 9.

Harry doesn’t tell us his feelings directly: The tone of the limited third person narration does. It clearly is coloured by Harry’s own experience. The words ‘of course’ and ‘but to ignore it completely’ could almost be Harry’s own voice, his own thoughts in italics.

Use emotive language in third person narration similarly to make your narration show narrators’ feelings.

2. Show the mystery of a limited point of view

Third person limited is a popular POV in mystery novels because when we don’t know what secondary characters are thinking and feeling explicitly, they remain an intriguing mystery.

Example: Showing another character’s unknown thoughts and feelings in limited third person

For example, we could have a scene where an investigator encounters a possible murder suspect:

Inspector Garrard watched the man behind the counter serving a customer. His movements were quick, almost agitated. As he approached he saw the man’s eyes flick to his chest, as though looking for a telltale badge. Or was he imagining things, the man had glanced down out of shyness?

Here, we only know what the detective sees and guesses. We see him actively reading people’s body language and giving it meaning.

Because he’s looking for a suspect, the man’s smallest gestures – movements, where he looks – seem suspicious. Yet our viewpoint character’s perspective is warped or rather shaped by his current focus – catching a culprit. The man could be wholly innocent.

Third person limited lets us feel the tension of how ‘unknown’ another person – a ‘not-I’ – may be. Because we don’t know with certainty their private thoughts and opinions.

3. Show characters’ mistaken assumptions

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813) is an excellent example of how you can use limited third person to show assumptions and the surprises they lead to.

Just as the inspector in the above example assumes or imagines guilt based on telltale signs in a person’s behavior (e.g. nervous movement), your limited third person narrator can assume the worst (or best) through limited information.

Example of assumption in third person limited narration

In Pride and Prejudice, Austen uses limited third person narration to describe Elizabeth Bennet’s first impressions of her eventual love interest, Mr. Darcy.

We first meet Darcy at a dance. Darcy dismisses the idea of dancing with Lizzie to his friend. Lizzie overhears:

“She is the most beautiful creature I ever beheld! But there is one of her sisters sitting down just behind you, who is very pretty, and I dare say very agreeable. Do let me ask my partner to introduce you.”

“Which do you mean?” and turning round he looked for a moment at Elizabeth, till catching her eye, he withdrew his own and coldly said: “She is tolerable, but not handsome enough to tempt me; I am in no humour at present to give consequence to young ladies who are slighted by other men. You had better return to your partner and enjoy her smiles, for you are wasting your time with me.”

Mr. Bingley followed his advice. Mr. Darcy walked off; and Elizabeth remained with no very cordial feelings toward him.

Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice (1813), p. 9.

Note the emotive language in Austen’s third person description of Darcy. He ‘dismisses’ the idea of dancing with Lizzie; ‘coldly’ withdraws. These coupled with his spoken words convey icy superiority – but this is all Lizzie’s POV, shaped by the perceived insult regarding her appeal. A

Although to Lizzie Darcy ‘withdraws’ his gaze, he could just as easily be looking away out of shyness. Lizzie interprets the gesture together, however, with his indifferent-seeming words. This shows how effective limited third person can be in showing how people evaluate each other using the limited information they have.

It’s only later in the novel that we see the kindness and warmth Darcy is capable of and recognize his aloof mannerisms as signs of a serious, passionate yet socially awkward character.

[Discuss POV and more in an online writing group where everyone shares the same goal – finishing a novel.]

4. Contrast limited viewpoints to show contrasting experiences

In third person limited, although your narrator occupies a limited viewpoint in the scene, showing the reader only what a single mind sees, hears, thinks and assumes, you can still alternate between viewpoint characters from section to section.

The advantage of this approach is that you can show the beliefs and assumptions of multiple characters as they interact with others with partial, inherently flawed awareness.

Get constructive feedback

Get helpful feedback from the Now Novel community with a free account, and pro feedback when you upgrade.

JOIN NOWExample: Contrasting third person limited viewpoints in Love in the Time of Cholera

Gabriel Garcia Marquez uses this potential of third person limited to excellent effect in Love in the Time of Cholera (1985). His epic romance tells the story of unrequited love when two would-be lovers cross paths again much later in life.

Early in the novel, Florentino Ariza confesses his love to the obsession of his youth, Fermina Daza. Yet with very poor timing – at her husband’s wake:

“Fermina,” he said, “I have waited for this opportunity for more than half a century, to repeat to you once again my vow of eternal fidelity and everlasting love.”

Fermina Daza would have thought she was facing a madman if she had not had reason to believe that at that moment Florentino Ariza was inspired by the grace of the Holy Spirit. Her first impulse was to curse him for profaning the house when the body of her husband was still warm in the grave.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Love in the Time of Cholera (1985), p. 50.

We see Florentino’s besotted gestures, but through the disbelieving, critical eye of Fermina.

In the next chapter, we see more of his view. Florentino remembers the first time he saw Fermina:

As he passed the sewing room, he saw through the window an older woman and a young girl sitting very close together on two chairs and following the reading in the book that the woman held open on her lap […] the girl raised her eyes to see who was passing by the window, and that casual glance was the beginning of a cataclysm of love that still had not ended half a century later.

Love in the Time of Cholera, p. 55.

Throughout the novel, Marquez alternates the less romantic views of Fermina and the dogged, obsessive romantic viewpoint of Florentino.

The contrasts between how they interpret their encounters and the meanings they attach to them create a strong impression of two different characters with individual quirks, strengths and weaknesses.

Get writing feedback on your limited third person use, and pro feedback when you upgrade your membership.

30 replies on “Writing third person limited POV: Tips and examples”

Do you have any tips on how to choose the appropriate POV character? I’m currently editing my fantasy novel and I have 5 POV characters so far. I tried to lower the amount but it’s not possible unless I delete an arc.

I read your article on how to use multiple POV characters. I have a lot of POV errors including head hopping unfortunately.

Hi Marissa, that is a tricky thing to juggle, but with an omniscient (i.e. non-involved) narrator you can move between characters’ viewpoints and impressions without it being too disorienting for the reader.

The advantage of an omniscient narrator is that you can also give the reader details about your world inside the main narration without having to reserve this information for a prologue or appendix. You may find this post on using omniscient narrators helpful: https://www.nownovel.com/blog/omniscient-narrator-examples-tips/

Have a lovely weekend.

I have a question. So if I’m writing third person limited POV, how would I refer to the main character’s parents? Would it be mother or her mother? Also her sister is sometimes in the scene with her, so how would I refer to them in these scenes. Would it be Krystle’s parents, or her parents, or their parents?

Hi Leslie!

Thanks for asking. That’s an interesting question. It depends on how much narrative distance you’d want from the character. If you just used ‘mother’ and ‘father’ more without the pronoun it would make the narrator feel closer to first person. E.g. ‘Mother had given her a lecture again that morning’ reads as a little closer to the character’s own voice than ‘Her mother had given her…’. This is likely because in first person we might drop the possessive pronoun ‘my’ and write ‘Mother/Mom gave me a lecture again this morning’ (and not ‘My mother…’) so the sentence reads almost as though it is in first person at first.

Also, you might use the one without pronouns more if ‘Mother’ and ‘Father’ were the given character names in the story (e.g. in E.L. Doctorow’s novel ‘Ragtime’ the characters have names like ‘Mother’, ‘Father’ and ‘Mother’s Younger Brother’. This gives them a sort of ‘everyman’ quality.

I hope that helps!

thank You was helpful

It’s a pleasure, Kuda! Thank you for reading our blog.

Third person limited differs from omniscient third person because the narrator is an active participant. I am a little confused by this sentence, can you please provide an example or clarify – I’d really appreciate it. When I think of actively participating narrator I think of either 1st person (because they are telling the story themselves) or possibly a narrator in 3rd person limited or omnicient when they break the 4th wall to address the reader or supply their own oppinions/thoughts, even if they are not a chracter in the story. Confused! Thanks!

Hi Quill! With pleasure. The difference is: In omniscient third person, the narrating voice can tell us what *any* character is thinking or feeling at a given point in the scene. The narrator is ‘God-like’ in that way that they are all-seeing. Yet they are not one of the characters. Tolstoy used this type of narrator a lot. In limited third person, narration is restricted to a specific, involved character’s POV. So say, for example, a boy sees a girl he has a crush on in his class at high school, if he is the viewpoint character, the author can only show the reader what the girl is thinking or feeling via what the boy sees, hears and interprets (the narration cannot access the girl’s thoughts and feelings as it is ‘limited’ to the boy’s POV).

Does that help a little?

That helps, thank you. Can you write in limited third person, but also, as the narrator, address the reader either directly or chime in with my own thoughts and opinions? Would this still be third person limited?

Also, in general, I am having difficulty deciphering when a narrator is telling us what is happening, and when we are reading what the character is thinking or feeling. It’s a confusing questions to try to put into words, and I’m probably over thinking it, but I haven’t been able to get passed this. I’ll use an example:

Benjamin picked up the pace on his way to the school bus stop. If he was late again, Mrs. Snim would be really mad.

Is the narrator is telling us that if Benjamin was late again, Mrs. Snim would be really mad, or are we witnessing what Benjamin himself is thinking and feeling?

Thanks!

Hi Quill, you can do that, though it’s perhaps a little outmoded (it was common in Victorian era novels that moralized along the lines of ‘Now listen, dear reader, why you should/shouldn’t do this or that’). The main point of third person limited is that it sticks to a single character’s consciousness so it would definitely break the effect. Omniscient third (being able to switch between third person view points at will, with no single character’s viewpoint guiding the story) might be better for that.

I’m writing in third-person limited with multiple POVS from chapter to chapter. The characters are mostly siblings. When I move from one sibling’s POV to another, do I write ‘their parents’ or ‘her/his (POV character) parents – given they are all in the same room.

Help would be appreciated. I’ve been very confused about this. Great article!

Hi Anya, thank you for your question and for the feedback.

It would depend whether at that moment in the story you are writing from one sibling’s POV or from a collective POV. Compare:

‘Anna wished her parents would stop embarrassing her at PTA meetings’ to ‘Anna and Sarah wished their parents would stop embarrassing them at PTA meetings’.

Alternatively, if you wanted to differentiate Anna and Sarah’s POVs if both are present in the scene, you could have ‘Anna wished their parents would stop embarrassing them at PTA meetings, while Sarah just wanted their dad to stop clearing the dance floor at every wedding the family attended.’

Here the plural pronoun would make sense as the two sisters’ individual views about a shared object are presented (making the plural ‘their’ read fine, because the sisters are being spoken of together). It would also help to avoid the ambiguity of using ‘her’ for each character, as this could be misread as Anna and Sarah having different dads.

So let whether the narration is describing a single character’s viewpoint or a shared or grouped viewpoint (or object) be your guide. I hope this helps!

I have a question about something I’ve gotten into heated debates over:

I think that writing from the third person limited point of view of an unsavory character does not mean the author implicitly endorses that character. Even if the character doesn’t learn better by the end of the story, the author and the character are separate.

This applies to thoughts that are racist, misogynistic, etc.

A frequent example is teenage boys checking out teenage girls. People often call this writing pedophilic. But I can remember being a hormonal teen and what girls looked like to me.

Hi Nate, thank you for sharing that. I agree with you that characters should not necessarily be taken as representative entirely of the author. A big part of storytelling is imagining otherwise, imagining what is different to your own experience. For example, Vladimir Nabokov created Humbert Humbert who is a pedophilic narrator in Lolita, which was of course very controversial at the time and still is to this day. When an interviewer asked him what his inspiration for the story was, he told an anecdote he’d heard about a chimpanzee who’d been given art materials and drew a picture of the bars of their cage/enclosure.

In a way that says a character (like a person) has a fixed frame of reference and conscience, so to a racist or misogynistic character, they’re only seeing the bars of their own cage, their own way of thinking. Showing this doesn’t necessarily mean the author’s cage has the same bars. But it’s also worth thinking about art in terms of ‘responsibility’. For example, is it socially responsible to center hateful (racist or other) voices in the world (or are there enough of them rioting, forming mobs, spreading propaganda?) It depends on the purpose of your story (for example, you might want to show how a racist is formed, where they go wrong, but from their viewpoint). It does take a lot of wisdom, maturity and skill to do this well.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts.

Do you have an article on how to write third person close (third person deep), I searched nownovel but could only find this post. I also searched google and found a few articles, but I am still struggling on how to write it

Hi Marissa, thank you for asking. You may mean what we also often call ‘third person limited’? (Where third person narration is restricted to an individual’s viewpoint). We have an article on this here. I hope it helps!

I am working on a mystery in 3rd person limited, with 3 POV characters. I am looking for recommendations of mystery novels in this POV. I am particularly interested in how writers successfully handle exposition. None of my villains are POV characters and I don’t want to go in that direction. What to read?

Hi Andrea, thank you for your great question! I’d say it’s fine if none of your villains are POV characters as that does leave them with more mystery (if the reader has no access to what they’re thinking/feeling). They remain a big unknown ‘other’. There are some helpful examples of limited third POV in mystery in this article here over at Herded Words. Good luck!

A great story illustrating subtly using limited third to characterize from the start of the exposition is James Joyce’s short story Clay (though this is not a mystery).

[…] proceeds to give the reader fragments written in the third person, alternating with captioned photographs from his youth. For example, in one fragment titled […]

Thanks for the fantastic article, Jordan.

What do you think of mixing a first-person POV with a third-person limited POV via separate chapters? For example, my main character’s story is told in FP POV, but I want to achieve two things by writing the secondary character in third-person limited: create a sense of mystery and danger, since she has become involved, unknowingly, with an escaped convict; and to give the reader a break from the constant “me, me, me…I, I, I” FP narration of the protagonist. I feel the voice/tone would be identical in either instance, the only differences being the pronoun usage and perhaps a slightly more intimate feel to the FP voice (i.e. “I watched him evenly over my cup of tea” vs. “she watched him evenly over her cup of tea.”)

Essentially, I’m trying to decide if the secondary character’s chapters would provide more mystery and intrigue written in third-person limited versus FP. Or would this be too jarring for the reader to switch back and forth?

In my first book, I alternated between FP *past tense* POV for one character and FP *present tense* for a secondary character (though only four chapters out of 25); not a single reader complained about it, although when I read it now, I myself hate it! This is why, in my second installment, I want to get it right.

I would sure appreciate your opinion on this, Jordan, and am delighted you’ve kept the comments open after all this time :-.)

Hi MJ, thank you for the great, detailed question. Personally I find there’s a satisfying unity when different characters’ chapters use the same POV, and am concerned readers would indeed find the switch between first and third jarring, though I’m sure you wouldn’t be the first to do this (unfortunately I can’t think of any examples off-hand).

Part of what makes a book like Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying with its many viewpoint narrators cohesive is that each first-person narrator has a distinctive viewpoint, known name, position within the family, and a personality that comes through in part thanks to the ‘closeness’ which you describe being a particular property of the first person. This anchors each viewpoint in relation to the others; one can slip into each viewpoint comfortably without stopping to think ‘who is this now’ too often.

My advice would be to write a chapter in each POV and see how they read in succession. It would need to become clear early in the second chapter who the pronouns refer to in order to avoid any confusion about who is speaking and who the focal characters are in relation to the first-person narrator the reader has been introduced to already.

I hope this helps!

Yes, Jordan, this certainly helps.

After a ton of research on this subject, the consensus seems to be to stick to one POV. Thus, I’ve decided to write both characters in first person, being mindful to curtail the number of references to “me” or “I” in my prose. It’s definitely an art that other more experienced authors have mastered. They consistently use description of surroundings rather than inward feelings, as in, “The yoga studio’s temperature was set to 80 degrees, a level of heat only suitable for my grandma and incubating chicken eggs.” versus “I was so hot I thought I might pass out.”

Thank you for your great insight. Love reading all the great tips on this site.

It’s a pleasure, MJ. Great example! Exactly as you say, it’s a matter of capturing that character’s voice and turn of phrase which asks a lot more of a writer’s imagination (and also requires knowing your characters well). A useful exercise one could do would be, for example, to describe a room (like the yoga studio in your example) from first a pessimistic character’s POV, then an optimistic character’s POV, without using the words ‘me’ or ‘I’ once.

It’s fine to use these pronouns moderately. Another helpful strategy is to identify and remove ‘filter words’ (e.g. instead of ‘I felt that she was being unfair’, ‘How dare she!’ and so forth). Thank you for visiting us and taking time to share your feedback and questions!

Hi, Jordan.

I’m around halfway through my story, which is written in third person limited. I change character POVs for different chapters, but when in a chapter I maintain a single character’s POV throughout that chapter. If I change to a new character, I’ll use a scene break.

Here’s my problem:

The reader has, by this point, been introduced to all main characters, but the chapter I’m currently writing is from the POV of a main character who hasn’t yet met some of the others. Let’s call him Bob. Bob is tasked with finding a young woman in her 20s called Jill. He’s never met Jill and doesn’t know what she looks like. He knows that his adversaries, Dave and Pete, are also looking for Jill.

Bob arrives outside of a bar to see Dave trying to push a young woman in her 20s into a car. Bob can make a reasonable assumption the woman is Jill, so I’ve referred to her as such, even from Bob’s POV. Bob also sees his other adversary, Pete, trying to get a young man into the same car. The reader already knows this young man as Jack. But Bob has no awareness that Jack even exists at all. He makes an assumption that the young man (Jack) could be Jill’s brother or friend or boyfriend, but can’t even guess at Jack’s name, as Jack isn’t mentioned in Bob’s files.

Here’s my question:

How do I refer to Jack when I’m writing from Bob’s perspective? Can I still refer to him as Jack, even though Bob doesn’t know his name (but the readers do), or do I need to refer to (and continue to refer to) Jack simply as the young man until such time as one of the other characters says Jack’s name out loud, at which point Bob then knows it?

Any advice would be greatly welcome.

Thanks,

Dash

Hi Dash, thank you for sharing this question. That’s a complex and interesting scenario. I would firstly say definitely do not refer to Jack by name in Bob’s POV section if he does not know his name/identity (if you want to keep the chapter in Bob’s limited POV throughout) as this would make the reader think Bob does know Jack and his identity and perhaps become confused if this has not been shown or explained before.

One solution would be to cut the chapter/scene when Bob sees ‘a man’ being bundled into a car to have a new scene/chapter from either Jack’s POV (if he is a viewpoint narrator) or Pete’s POV (if he is a viewpoint narrator) so that your reader has the ‘aha’ moment of realizing the mystery man is in fact Jack. Here, switching viewpoints could thus be used for narrative irony; to show what Bob doesn’t know (but the reader does).

Another option would be to let the scene play out with Bob thinking about ‘the man’ or some other generic descriptor and later reveal the identity of Pete’s captive. You could also have Bob noticed a hallmark physical detail such as an item of clothing the reader may recognize from an earlier description of Jack, if you want the crossover to be subtler.

So there are several options. The other option you shared of one of the other characters supplying the information Bob needs by speaking Jack’s name could also work.

I hope this helps! Good luck.

Thanks, Jordan.

You’ve suggested exactly what I figured I would need to do, which is to keep Jack anonymous to Bob until Jack’s identity is explicitly revealed to Bob.

Thanks, mate.

Dash.

It’s a pleasure, Dash. Glad I could help! Good luck with your story further.

This article has been a great help. Thank you so much for putting the time in to write it.

Thanks so much David! Very glad to hear that it is helpful. All best with your writing!

Glad you found it useful, David. Thanks for letting us know. Happy writing!