What is rising action in a story? How do you make the build-up to the climax gripping, saturated with tension? Rising action is core to impactful dramatic structure. Learn all about it and read ten ideas and examples to make your story gripping:

What is rising action?

‘Rising action’ refers to narrative events that build towards climactic conflict and resolution.

The term ‘rising action’ is often attributed to the German writer Gustav Freytag. Keep reading for a concise breakdown of Freytag’s theories on dramatic structure, and how they continue to apply in modern storytelling.

Freytag’s theories of narrative structure and drama

In Freytag’s Die Technik des Dramas (‘The Technique of the Drama’), the author discusses story structure, with a focus on stage dramas.

In the second chapter, Freytag writes about the ‘play and counterplay’ of change and conflict in storytelling:

The structure of the drama must show […] contrasted elements of the dramatic joined in unity […] the accomplishment of a deed and its reaction on the soul, movement and counter-movement, strife and counter-strife, rising and sinking, binding and loosing.

Gustav Freytag, translated by Elias J. MacEwan, ‘Chapter II. The Construction of the Drama’, in The Technique of the Drama, p. 104 (1894)

How does this sense of push and pull relate to rising action? Keep reading for more ideas and examples:

Five parts and three crises of drama

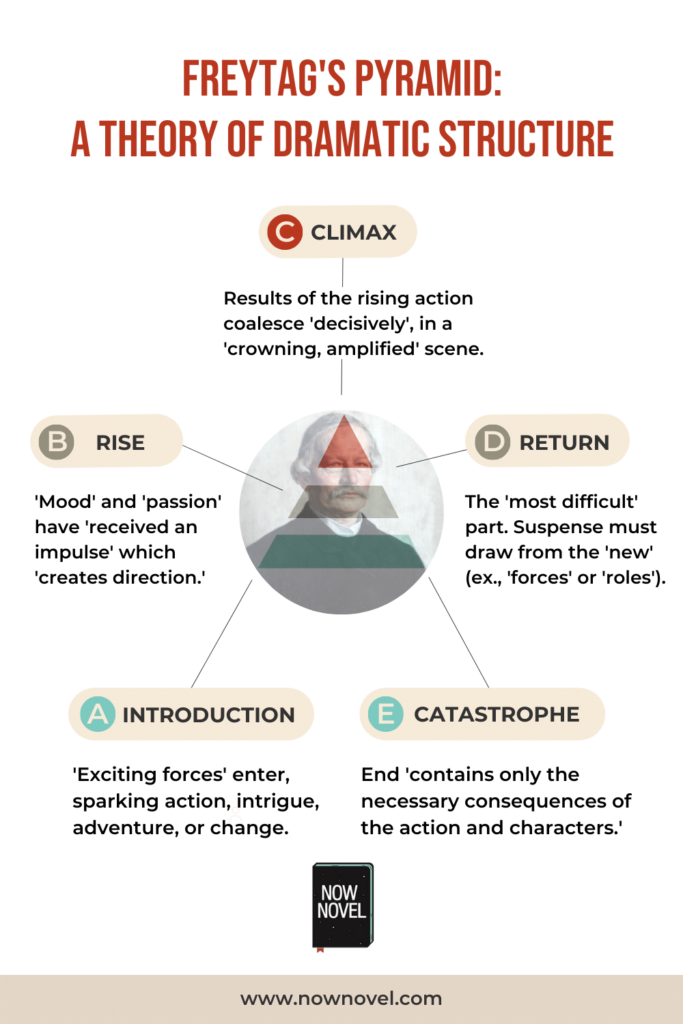

In a section titled ‘Five Parts and Three Crises of the Drama’, Freytag diagrams rising and falling action. This has become known as ‘Freytag’s pyramid’. He writes:

It [drama] rises from the introduction with the entrance of the exciting forces to the climax, and falls from here to the catastrophe. Between these three parts lie […] the rise and the fall. Each of these five parts may consist of a single scene, or a succession of connected scenes, but the climax is usually composed of one chief scene.

Freytag, pp. 114-115.

An illustrated version of Freytag’s pyramid diagram:

Freytag calls the final section of dramatic action ‘catastrophe’ because he mostly examines tragic drama which typically ends with a tragic fall. You could replace his term here with ‘resolution’.

Read how Freytag describes rising action, if you are interested to learn more. He gives an analysis using Shakespeare’s plays on pages 125 to 128. Google has made the translated 1894 edition free, and you can download it as a searchable EPUB or PDF. Here is a more detailed look at Freytag’s Pyramid.

It is worth adding that stories featuring what could be called rising action exist in many even older storytelling and mythological traditions, outside western, European, and English writing traditions.

Rising action’s function – a summary

From the above, we can summarize:

- Rising action begins from the story introduction. Here, ‘exciting forces’ emerge and set off sequences of ‘play and counterplay’ (action and reaction).

- It introduces events that build to a climactic scene. For example, a major confrontation. E.g., hero vs villain, or a would-be lover confronting the decisive moment of whether they will accept a proposal. The climactic scene isn’t necessarily one of aggressive confrontation. It could depict an internal struggle.

- Rising action may consist of a single scene, or a series of connected scenes in a longer story or form.

- It creates unity or cohesion, by pairing actions and reactions and showing the push and pull of desire and obstacle.

Let’s explore ten ways to make your rising action thrill readers:

How to create rising action driving drama: 10 methods

Here’s how to build rising action that milks tension, emotion, and suggests what’s at stake:

- Build emotion using goals and motivations.

What do your characters want, and why do they want it? An emotional stimulus into rising action makes your reader invest.

- Add setbacks and complications for uncertainty.

What obstacles thwart your characters? Ensure paths to base camps and summits aren’t easy.

- Spike suspense using play and counterplay

Compelling rising action is chess-like. Show the consequences or repercussions of individual turns, decisions.

- Build suspense with repetition and variation

Take, for example, the simplicity of the fable of the three little pigs. Each foiled attempt to stop the wolf creates suspense for his next attack.

- Show or imply what’s at stake (and raise the stakes)

What is the absolute worst case scenario if your character doesn’t win, get what they want, in a climactic scene? Show or imply risks and fears.

- Escalate tension using urgency

Give rising action time-bound (or urgency varying) pressures that make readers sweat like bomb disposal technicians.

- Twist what the reader thought they knew

Maybe a sign your character read one way turns out to mean something completely different as your story’s action rises.

- Leave open loops to create burning questions

Tease readers with hints at pending revelations. Give your reader gaps like crossword answers they’re dying to fill in.

- Escalate intensity in rising events

Rising action inclines and does not plateau. Try escalating intensity so that each peak beckons to the next (or threatens a farther way to fall).

- Stay riveting with reversals

Sudden turns of fortune (for better or worse) make parts of a story change in explosive ways. Play with rupture-like events.

Keep reading for a brief examination of each rising action idea above.

Build emotion using goals and motivations

There can be no rising action without characters’ goals, dreams, and desires. Motivation is the prequel; doing, the sequel.

Tweet This

Your characters’ goals and motivations are part of another triangular aspect of story: Goal, motivation, and conflict.

Goals and motivations are part of what makes us care about characters, and invest in their journeys.

We care about the eco-activist determined to bring down the corporation poisoning a small town’s water source. We care about the reluctant hero who accepts the quest because they abhor tyranny or wish to protect their homeland.

To create rising action that has emotional heft:

- Gives characters values, fears and flaws. What matters to your main characters? What are they most afraid of as complications and setbacks start creating hardship? Creating a character profile (which you can do in the Now Novel dashboard) will help.

- Build motivations from desires and wounds. Why do your characters want what they do? What are they passionate about? What trauma or wound has made them vow ‘never again’ or vow to achieve something?

- Ask why your character must act. Why can’t your character ignore their call to adventure or action (be it following up with a potential new love interest or pursuing a dangerous quest)?

The path to love, success, or peace, is hardly ever smooth. Keep reading for tips to add setbacks and complications that give action a gripping incline.

GET YOUR FREE GUIDE TO SCENE STRUCTURE

Read a guide to writing scenes with purpose that move your story forward.

Learn moreAdd setbacks and complications for uncertainty

Setbacks and complications give rising action uncertainty. Uncertainty creates demand for answers to keep readers turning pages.

What should you use as setbacks in your rising action? Find situations that lie on a spectrum of severity.

Tweet This

To illustrate, there’s an old joke about country music’s typically maudlin subject matter. ‘What happens when you play a country song backwards? You get your wife back, your house back, and your car back.’

Some losses are material, others, immeasurable.

A tragic story about a professional who makes the wrong choice (for example, a phony inventor who defrauds investors) may begin with a smaller loss (a job). Setbacks may progress progress to larger ones (decimated reputation, future prospects).

The restorative path for each magnitude of setback involves different degrees of difficulty, different internal and external conflicts and barriers. Use little tremors and big earthquakes.

Example setback in romantic rising action: Pride and Prejudice

In a romantic story, the first rising action often reflects the messy, awkward, unpredictable beginning stages of love.

This time in a new relationship is fertile ground for misunderstandings and doubts.

Even the classics (and not only modern love stories) have clear rising action.

In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813), for example, Elizabeth Bennett initially thinks Fitzwilliam D’arcy is an arrogant jerk. due to the dismissive way he speaks about her (which she overhears at a dance).

This initial encounter is a setback and complication in Lizzie and Mr. Darcy’s romantic arc, as it fixes Lizzie’s unfavorable view of Darcy’s character, at first.

The rising action of repeat encounters (involving complications such as the scandal of Lizzie’s sister’s elopement) cause Lizzie to reassess Darcy’s character. Yet this ‘second chance’ has its own setbacks.

For example, there is further complication when Lizzie rejects Darcy’s first proposal. In making it, he insults her family and social position.

Setbacks and complications often cut to characters’ cores, especially in character-driven genres such as romance and tragedy. They make characters relatable, since most readers will have experienced painful setbacks of their own.

Spike suspense using play and counterplay

‘Play and counterplay’, to go back to Freytag, have a vital role in rising action: They spike suspense.

Think of play and counterplay, action and reaction beats, as a game of chess. One player may be calculating and strategic, the other impatient and reactive. One may sacrifice pawns to topple bishops, the other might safeguard every single piece.

Suspense in rising action builds through the uncertainty of these plays and counterplays. Complex dynamics between characters with different or opposing styles, demeanors, desires, willingness to make sacrifices.

In conflict-driven rising action, who makes the first misstep? What will be the most immediate consequence (or a later one)?

To build suspense in rising action;

- Play with size of action and reaction. For example, if the conflict in your story is primarily relationship conflict, maybe one character is new to the other’s triggers, and is surprised by an excessive-seeming reaction for what they thought was a minor wrong or mistake

- Give actions consequences and repercussions. As a consequence for the example above, a hurt character may lash out, run away. Negative or even dire consequences introduce further unknowns – how (or whether) everything will resolve

Build suspense with repetition and variation

If you’re writing in a genre that requires dread and suspense (for example a thriller), repetition with variation that implies precariousness is one way to make rising action gripping.

The simplest example of this is the dramatic structure of the fable of the three little pigs.

The first pig builds their house with straw, so the antagonist, the wolf, gets in and devours them. The second uses sticks – same outcome. The third, by building their house with bricks, thwarts the wolf.

Each successive visitation by the wolf generates suspense because we know what failure on the pigs’ part means. We understand the serious, mortal stakes.

In a thriller, you might show a stalker’s repeat spying. In a horror, a character’s recurring sensation they’re being watched. Repetition is a great tool for tension (as well as comedic writing).

An example of rising action in a thriller

In Paula Hawkins’ novel The Girl on the Train (2015), the protagonist Rachel Watson spies on her husband Tom, who has left her for another woman, Anna. The situation fuels Rachel’s spiraling into alcoholism.

As the story unfolds, we see Rachel harassing Tom and Anna. The tension Hawkins creates through Rachel’s actions makes the rising action from inciting events tense.

A rising action complication: Through her obsessive spying on Tom and Anna, Rachel starts uncovering unnerving details about the lives of another couple living nearby. She’s slowly entangled in additional lives and lies.

These complications provide rising action as Rachel must decide what to do with unsettling information she gains through spying.

What this example teaches about rising action:

- Rising action moves narrative towards a point of higher suspense and more urgently required action. Rachel cannot ignore the troubling information she starts piecing together.

- Rising action adds complications and stakes. Because of Rachel’s addiction and shaky boundaries, the reader might wonder how much of Rachel’s narration is reliable. They may also wonder what repercussions her prying and grasping behavior will bring.

What about stakes, how could you use these to make rising action intriguing?

Show or imply what’s at stake (and raise the stakes)

As your story hurtles towards a climax, the reader should ideally have an idea of the best and worst-case outcomes. Best case? New houses keep wolves at the gate. Worst case? Bad news for porcine populations.

Tweet This

Your rising action should show and imply what your main characters could lose if it all goes wrong.

Worst-case scenarios range from the ‘unhappy-for-now’ (for example, a love affair not working out) to death and other grave disasters.

Stories have stakes because characters stand to lose things such as:

- Life

- Love

- Work

- Pride

- Confidence

- Stability

- Security

- Power

- Health

- Reputation

Rising action gives the opportunity to show your character losing their grip on any of the above, or other things they value.

Stakes are closely related to personal fears. For example, we might fear not only losing a lover, but also never finding a relationship again.

Understanding the matrix of drives, fears and stakes in your character’s mind helps you create powerful psychological realism and more riveting rising action.

Escalate tension using urgency

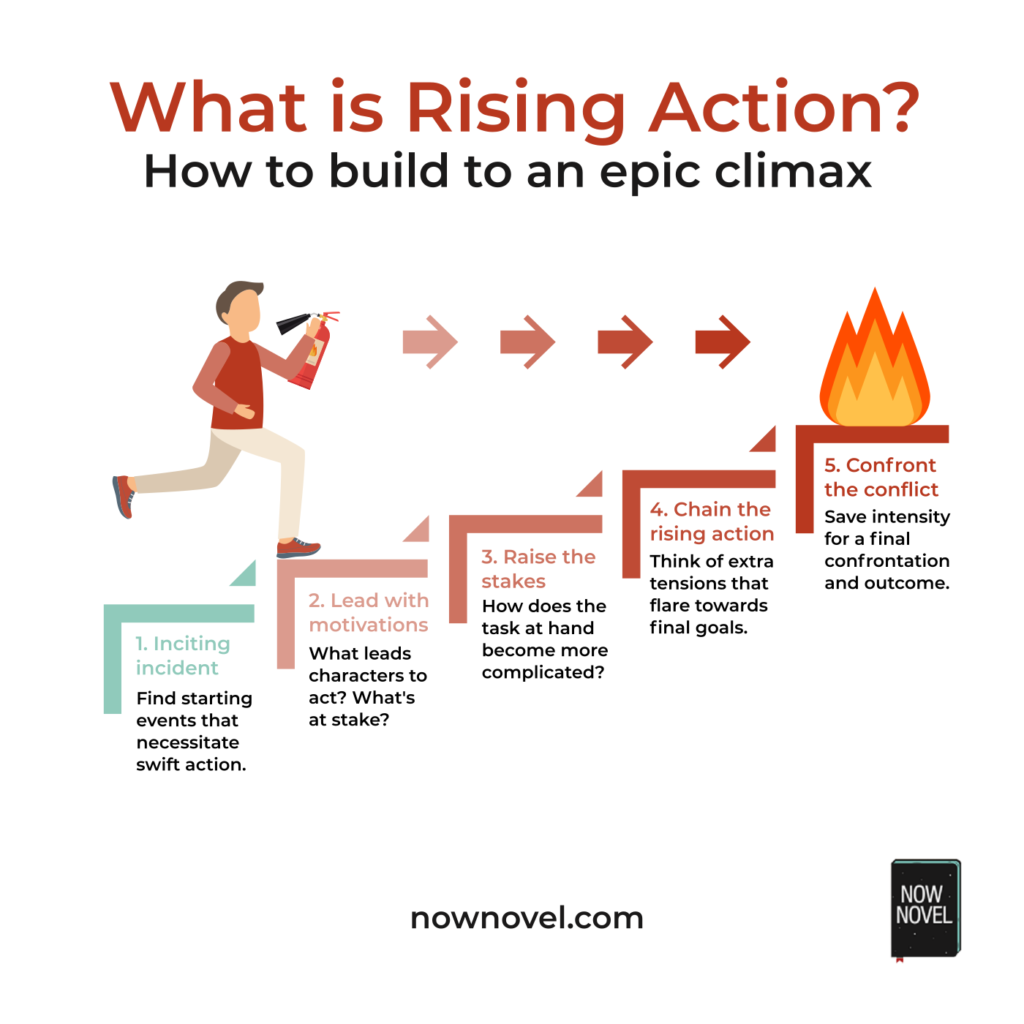

In the progression from inciting incident to climax, pace and the intensity of change are important. Tasks and trials typically lie on a spectrum or urgency.

In Star Wars: The Force Awakens, the scavenger Rey stealing the Millenium Falcon to escape Jakku (with help) creates one level of urgency.

Later, Rey finds Luke Skywalker’s lightsaber in a secluded vault, leading to disturbing visions that cause her to flee into the woods alone. That’s another level of urgency.

As you write scenes that move your story closer to the climax, remember play and counterplay.

In the above blockbuster example, there are trials faced together, and trials faced alone. Some flights are deliberate escapes, while others involve greater terror, bewilderment, and haste.

Twist what the reader thought they knew

Plot twists in rising action keep progression to your story’s climax unpredictable and mysterious.

For example, the DI investigating a murder case might discover a new alibi. They find absolute proof the prime suspect isn’t ‘the one’, which bumps them to the bottom of the suspect list. It could also turn out that this proof was flawed, reinstating suspicion.

Twists that occur in the course of rising action are useful because they:

- Keep your reader guessing. A completely predictable arc would risk becoming boring.

- Broaden story possibilities beyond your climax. Freytag writes about the difficulty of the ‘return’ or falling action (pp. 133-135). The challenge of creating suspense once a major climax has occurred. He says you need to craft suspense from ‘new’ material after the climax, new roles and forces. Twists in rising action help to set up said roles/forces that may return later.

- Introduce new setbacks and solutions. For example, maybe the investigating officer on a case makes an error in judgment leading to their suspension. Yet there’s a twist whereby this situation (for example, a shadow investigation they privately continue) provides them with a clue they wouldn’t have gained on the job.

Leave open loops to create burning questions

In video and podcast production, ‘open loops’ are teasers that keep your audience engaged. A similar term in narrative storytelling is the ‘hook’ of a scene or story.

Example open loop: ‘Keep reading to learn what you could be getting wrong in your rising action.’

Example story hook: ‘As I exited the metro, I grew aware of footsteps just behind me, matching my pace as I sped up. I crossed over the road, swallowing the urge to look back.’

Think of hooks in terms of the implied open loops they set up. For example, you could write the story hook example above as an open loop:

‘Keep reading to find out whether the commuter is being followed, and by whom.’

Your rising action is the place to build up reasons to keep reading. Make your reader ask questions such as:

- Where and when will the action reach a climax, will the final showdown occur?

- What could be a negative outcome of the climax, knowing preceding events and the protagonist’s fears?

- After the climax, what further work, return, sacrifice or other further action will still be necessary?

Create open loops using strong hooks that propel readers towards future events. This gives rising action a sense of momentum and purpose.

Example: Creating an open-loop-like hook that teases conflict

In the prologue to George R. R. Martin’s bestselling epic fantasy classic, A Game of Thrones, revelations from prologue to first chapter already create a sense of rising action.

The prologue fits Freytag’s theory of introductions to an extent. Exciting forces enter, their exact nature initially mysterious.

We learn that ‘wildlings’ are presumed dead and a group of men are patrolling the region beyond ‘The Wall’. A character named Will has the unsettling sense he’s being watched by some hostile force, the mood shifting in the area Will has patrolled for the past four years:

He was a veteran of a hundred rangings by now, and the endless dark wilderness that the southron called the haunted forest had no more terrors for him.

George R. R. Martin, A Game of Thrones (1996), p. 1.

Until tonight. Something was different tonight. There was an edge to this darkness that made his hackles rise.

The prologue hooks the reader by implying troubling change. We ask what ‘wildlings’ are, what could be watching Will and his party.

You could express the ‘open loop’ for the prologue thus: ‘Keep reading to find out what ‘wildlings’ are, who the men who patrol The Wall are, and what life-threatening forces lurk in their world.’

Example: Making rising action answer questions as it creates others

Rising action in Martin’s first chapter develops established unknowns from the prologue while creating further questions.

We shift to the viewpoint of a seven-year-old child named Bran, who is riding with a party to see a man beheaded.

We learn that Bran’s father will be the one to execute the man. Bran initially thinks it is because the man was a wildling (who are fabled to snatch people), but his father tells him the real reason was the man was an ‘oathbreaker’ who deserted the Night’s Watch (the patrolmen of The Wall introduced in the prologue):

“He was a wildling,” Bran said. “They carry off women and sell them to the Others.”

Martin, p. 12

His lord father smiled. “Old Nan has been telling you stories again. In truth, the man was an oathbreaker, a deserter from the Night’s Watch. No man is more dangerous. The deserter knows his life is forfeit if he is taken, so he will not flinch from any crime, no matter how vile.”

As Martin establishes the ensemble, rising action starts to show the ‘mood’ and ‘impulse’ that spur actions in Martin’s world. Loyalty is everything, a matter of life or death. The wrong choice can quickly cost characters their heads.

The first chapter’s rising action begins answering the prologue’s most pressing questions. We learn more about wildlings and the men who patrol the wall.

Escalate intensity in rising events

A ninth way to make rising action build momentum and suspense is to escalate intensity.

As your chapters develop, think about ways you can increase the emotional, visceral intensity of events.

For example, you could make rising action more intense by:

- Taking your characters from intense team challenges to solo, unaided ones (like in the Star Wars example above)

- Making complications and setbacks add increasing constraints (familiar tools, weapons, ways, support lie out of reach)

- Progress towards increasingly precarious settings (e.g. hiking from base camp to Everest’s peak, or straying further beyond The Wall)

The relentless procession of tasks of increasing difficulty is a rising action device you find in many stories. The Greek myth of the twelve tasks of Hercules, for example.

The difficulty of Hercules’ tasks (or ‘labors’ as they’re often called) increases until he must go down into the underworld (Greek mythology’s version of hell) itself.

Stay riveting with reversals

Finally, rising action may startle or surprise with reversals – sudden changes of fortune for better, or for the worse.

Take, for example, when the mentor figure of Gandalf is swept off the bridge into the depths in the conflict with the Balrog in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings fantasy cycle.

This major reversal affects what guidance the protagonist has access to. It appears without fanfare or warning, making the way ahead more dangerous in an instant.

Author Alexa Donne discusses reversals and ‘pinch points’ (relatively small turning points that point towards a story’s main conflicts) on her YouTube channel.

Need help creating compelling action? Join the Process for weekly editorial feedback, regular live feedback workshops, and webinars with authors, editors and other writing professionals to boost your storytelling skills.

FAQs on writing rising action

Since short stories have less space for development, your rising action might unfold over a single scene or two (instead of over several chapters). Read short stories and make notes on where rising action kicks off, where the impulse that creates direction grows.

The inciting incident is an event that spurs or catalyzes action. It’s like a bridge between your introduction (with the intro to ‘exciting forces’) and rising action. Rising action is the story segment where your character has found their reason to depart or act, through the inciting incident, and has started to move, change, grow, pursue their goals.

Exposition introduces, is introductory. Rising action develops, is developmental. Exposition may introduce names, settings, roles, scenarios. Rising action explores the plot possibilities (actions, reactions, choices, decisions) exposition has set up.

4 replies on “Rising action that grips readers: 10 epic climax tips”

This is extremely helpful. I had a sense of rising action in the inter-related story arcs of my two main characters, but this helps me build the rising action more deliberately. I love the suggestion for blending shorter periods of rising action (i.e., confronting unexpected challenges) with the characters’ main goals. And the advice, “Litter [their] with roadblocks, detours and dead ends,” is clear and easy to remember.

I’m glad to hear it was helpful, Jim. I’m glad you’ve found actionable ideas on rising action, too. All the best for finishing your current project!

I can read this article in the morning this article is very good to gain information.

Hi James, so pleased to hear that! All the best with your writing.