Learning how to write a novella is excellent preparation for writing your first novel. It enables you to work out characters and themes more extensively than a short story does. Writing a novella gives you helpful scaffolding for an expanded and more detailed book or series. Read on for a history of the novella definition of the novella and essential tips for writing one

A history of novellas

A short but powerful form, the humble novella has long roots that stretch all the way to the Italian Renaissance. It began developing in Italian by the fourteenth century writer, Giovanni Boccaccio, who authored The Decameron (1353). That book is a collection of tales told by seven young women and three young men in a villa outside of Florence, as they try to escape the Black Death. Spain’s Miguel Cervantes wrote Novelas ejemplares (1613), which focused more on human background and character development. Voltaire’s satirical novella, Candide, is another early example. Shakespeare and other writers borrowed plotlines from Italian novellas. The form was developed further in the late 18th and 19th centuries by writers such as Henry James.

Defining the novella

The novella is a work of fiction that is longer than a short story but shorter than a novel. The acclaimed author Ian McEwan describes the novella as ‘the perfect form of prose fiction’. McEwan suggests that the average length for a novella is ‘something… between twenty and forty thousand words, long enough for a reader to inhabit a world or a consciousness and be kept there, short enough to be read in a sitting or two and for the whole structure to be held in mind at first encounter.’

The novella is a work of fiction that is longer than a short story but shorter than a novel. The acclaimed author Ian McEwan describes the novella as ‘the perfect form of prose fiction’.

Tweet This

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America Nebula Awards define the novella as having a word count of between 17,500 and 40,000 words.

Writer’s Relief extends the upper word count limit of a novella, saying ‘The exact word count is not set in stone: 30,000 to 60,000 words may be an appropriate length.’ Whichever word count range you take as your guide, there are several important ways in which novellas differ from standard-length novels.

Types of novellas

Before we delve into the more granular details of novellas, let’s briefly look at types of novellas.

Literary

These are generally centred around psychology and character development. They sometimes do not have a fully developed plot, choosing to focus on the above points instead. They can also be quite experimental or avant garde. Examples include The Fox and The Ladybird by DH Lawrence, The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka, An Island by Karen Jennings, A Woman Destroyed by Simone de Beauvoir and Annie John by Jamaica Kincaid.

Inspirational

As the name suggests, this novella packs an inspirational message into its page. Its tone can be light-hearted. Examples include Jonathon Livingstone Seagull by Richard Bach, Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist, and The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. They are sometimes shorter than ‘regular’ novellas.

Genre

Horror, romance, thriller, science fiction, fantasy, steampunk, you name it. Genre novellas are popular among readers. Examples include The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, Binti, an African futurist science fiction horror novella by Nnedi Okorafor and My Funny Valentine by Debbie Macomber.

The architecture of the novella: Structure your novella expertly

As McEwan says in his piece for the New Yorker, ‘the architecture of the novella is one of its immediate pleasures’. The author describes how many novels feel as though they could have done with a good edit and feel longer than they should have been. The length of the novella demands that you cut away all excess fat from your story to leave something lean and appetizing. He says, ‘I believe the novella is the perfect form of prose fiction. It is the beautiful daughter of a rambling, bloated, ill-shaven giant (but a giant who’s a genius on his best days).’

When you plot a novella, think about all the things a lower word count demands. Typically, a novella (compared to a novel) is likely to have:

- Fewer characters

- Fewer changes in setting

- A clear central idea that is ‘always exerting its gravitational pull’ (McEwan)

This third point is perhaps the most crucial for planning your novella’s structure: How will you make sure that the central idea is in focus at all times, without subplots making your book feel like a mish-mash of ideas?

For an example, consider Ray Bradbury’s classic dystopian novella, Fahrenheit 451. At 46,118 words, it is comparatively short. But Bradbury packs in important social commentary.

Set in a future American society where books are outlawed and are burned if found, the story carries this strong central idea (the danger of state-based censorship) to a gripping, conflict-laden end. It is planned around a three-scene arc.

The first establishes the central idea (the book-destroying society in which Bradbury’s protagonist Guy Montag lives) as well as basic relationships between Guy and his wife and Guy and a teenage girl who lives next door.

The second section of the book broadens the cast of characters, introducing new pivotal actors in the story. Guy’s growing resistance to the status quo becomes more apparent.

The third section of the book sees intensifiying conflict as Guy has to make drastic choices. Tension rises to a height before the story is resolved.

Use characters economically

Historical fiction such as Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall allows family trees and scores of complex relationships, but novellas require a trimmer cast. Because you have less space to digress and expand, you need to focus on developing a handful of characters well.

The central cast of Fahrenheit 451 consists of just 10 people, including the protagonist Guy Montag. Each character is not given extensive backstory, and some (the protagonist Guy, for example) are developed more than others. Characters serve essential functions. They might act as catalysts for the protagonist to change their outlook and life (the neighbour Clarisse) or as challengers who thwart his new goals.

If you’re writing a novella, use character economically by:

- Identifying the crucial contribution each character will make to furthering the story and developing the central theme (will the character help or hinder your protagonist?)

- Give each character just enough dialogue and description to further the plot and create a vivid sense of your novella’s world.

Work out each character’s role as you would an actor’s in a play: Like the cast of a play, they have limited lines to get across their motivations and their purpose to the story.

Once you have outlined your story’s central characters, pay attention to your central conflict.

Give your novella a single central conflict

Like a novel, a novella should have conflict and tension (not necessarily physical, it can be a character’s internal struggle). Unlike a novel, in a novella there is usually one single conflict rather than multiple subplots that complicate the story. In Fahrenheit 451, the central conflict is Guy’s growing resistance to the culture of book-burning. In Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, the central conflict is the protagonist’s inner struggle caused by his obsession with a teenage boy (an obsession he restrains himself from acting upon) that develops while he vacations in Venice.

The central conflict or question of your novella should pull all the elements of the story into its orbit. Ideally, your novella’s central conflict should:

- Be satisfyingly complex yet allow resolution within 40,000 to 60,000 words

- Be interesting enough to sustain an entire story with no subplots

- Rise in stakes and anticipation over the first two thirds of the novella and be resolved in the third.

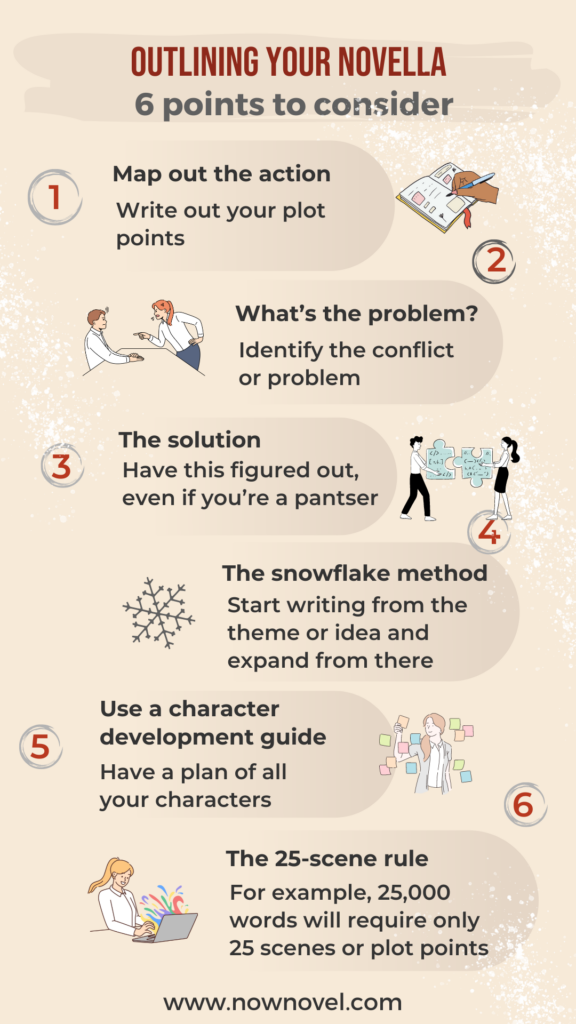

Here are six ways to outline your novella

Use plot points

If the snowflake method doesn’t work for you, try to map out your map out the action using plot points

A plot point is a point in the story that drives the narrative forward. As explained in one of our former blog posts, ‘A character hiding a gun in their glove compartment is a plot point. A character eating breakfast is not. Unless, to use a silly example, the first mouthful transports them to an alternate universe.’

Plot your points on a graph, it’s helpful to see this on a graph or use our scribble pad function.

There are commonly said to be seven main plot points:

- Exposition: Setting up the world you have created or the hook. This will include an inciting action.

- First plot point: A significant event in the story.

- First pinch point: This arises as a result of the first plot point.

- Midpoint: An action occurs that drives the story forward.

- Final pinch point: The character experiences another conflict.

- Final plot point: Here all appears lost.

- Resolution: This brings your story to a satisfying conclusion.

Bear in mind that you can play around and experiment with these plot points.

What’s the problem?

When you outline or start taking notes for a story, identify the conflict or problem. You can use the snowflake method above to figure this out in one line. Or, pretend you’re writing a blurb for your novella.

Figure out your solution

Have this figured out, even if you’re a pantser. Knowing your end point is, simply put, a good way to get there, even if you don’t want to outline your novella and want to discover where you are going as you write.

Use the snowflake method to outline

Developed by writer Randy Ingermanson, the snowflake method can be particularly helpful to writers who prefer to plan extensively before setting out to write a novel. There are 10 steps to the method. The writer begins by outlining the idea in one sentence , and moves from there to fleshing out the synopsis, characters, and scenes. For more on this method and how to apply it, read about the snowflake method.

Use a character development guide

Use a character development guide. You can open up a spreadsheet with your character’s names and motivations. You can choose to open up military-style dossiers on them. For an example of this, take a look at The Year of Living Dangerously by Christopher Koch. Although this is part of the novel’s stylistic device, you can adapt this to your own character bible. For example:

Bryant, Jillian Edith.

Nationality: British.

Born: 1938, under the sign of Pisces.

Occupation: Assistant to military attaché British Embassy, Jakarta.

Former postings: Brussels, Singapore. Little religious feeling… yet has a reverence for life. This is a spirit like a wavering flame… which only needs care to burn high. If this does not happen, she could lapse into the promiscuity… and bitterness of the failed romantic.

You can also make use of our character outlining system.

The 25-scene rule

Here’s an interesting way to plot our your novella, using the 25-scene rule.

Firstly, you may want to write your novella in chapters, or in scenes that follow each other without breaking it into chapters.

Writer Eva Deverell explains: ‘Scene lengths will also tend to be shorter in a novella. If we take 1000 words as a rough estimate for a scene, then a novella of 25,000 words will require only 25 scenes or plot points.’

So, if you want to write 40,000 words, consider mapping out that you will want to include 40 scenes.

Increase your novella’s pace

As writers for the MMU Novella Award point out, a novel can afford to develop in stops and starts and take the scenic route to the final climax. Not so for the novella. Because you have a primary story or character arc, it’s important to keep things building to a final climax, be it a blistering conflict or an inner development for your protagonist.

Pruning away subplots as suggested is one important approach to increasing your novella’s pace. One of the reasons writing a novella is great preparation for writing a novel is that it’s almost like outlining. Writing shorter sentences with the kind of concision you’d use in an outline will help you build better pace.

How to write a novella: Focus on the unities

Because you’re writing a story that lies somewhere between a novel and short story in length, remember to keep it simple. Barbara Monajem, recommends having ‘three unities in your novel:

- Unity of time: The story should take place in a limited frame of time

- Unity of place: The story should take place in one location [more than one location is fine too: Just make sure you don’t take up too much space explaining how your characters get from A to B]

- Unity of action: In Monajem’s words, ‘the conflict should be simple and easily resolved.’

Novellas in a flash

Here’s yet another way of writing a novella if you’d like to try something new. Instead of writing with plot points in mind, write a novella in small pieces of flash fiction, about 1,000 words, with a linked theme or idea, forming a cohesive arc. There needs to be a thread linking them: a shared location, a motif, or common plot events.

One example of this form is Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street. It is centered on a young girl, Esperanza Cordero, growing up in Chicago and is told through a series of vignettes. Other examples include Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill, Why Did I Ever? by Mary Robison and We the Animals by Justin Torres.

This process is explained well by writer Kieren Westwood in the video below:

Edit with ruthless precision

Remember what Ian McEwan said about longer novels often feeling like they could have used a decent edit? This is all the more important when writing a novella. In a shorter work, it is easier for readers to remember parts that bore in places or are overly wordy. Besides editing to get your novella within the necessary word count limit, edit to make sure that every page contributes to the whole. At every page turn ask yourself, ‘How does this scene fit into my central idea? What reason have I given the reader to turn to the next page?’

Where and how to publish novellas

Once you have written and edited your novella, you’ll turn your mind to publication. While genre publishers look on novellas more favorably than literary publishers, and you’ll have an easier time with placing genre novellas, there are other options.

You could self-publish a novella on Kindle, for example.

You can also choose to include a novella along with some stories, as was done in Nadine Gordimer’s Something Out There. Or, publish a collection of three to four novellas in one volume, as Mary Gordon does in The Rest of Life.

Consider submitting to Fairlight Books who publish a wide range of fiction including novellas. There are also other publishers who actively seek out novellas. Consider, too, that some literary journals also accept novellas for publication. Have a look at this comprehensive list of journals and some publishers. Here’s another useful list of publishers. And this one for where to publish novellas in a flash.

Competitions

Also keep a look out for novella competitions. There’s one for flash novellas. And here’s a worthwhile list of competitions to keep handy.

Although sticking within a 20,000 to 60,000 word count can be challenging, learning how to write a novella will improve your craft. Get started on outlining and honing your central idea with Now Novel.

*

Originally written by Jordan, this blog has been updated to include definitions of novellas and types, six new ways to outline a novella as well as information on where to publish and competitions to consider.

15 replies on “How to write a novella: 6 essential tips”

This was an excellent read, thank you!

Thanks so much, Hannah. It’s a pleasure!

Very nice! And useful too.

Thank you, John!

So this is not considered a series story, but a series of separate stories. What are your thoughts on turning a long novel type book into short series books like Harry Potter, or smaller instances like, Flowers in the Attic if a novel seems to be over whelming. Do series do better than a 5 lb. novel, or visa versa?

Did not mean to be confusing MY story is the novel wondering if it can keep readers attention with so many things going on at so many times flipping back and forth can make a reader put a book down for a snack and never come back. How do you get the reader to connect with the character in the first book? After she is a neurotic adult or while she is being abused to something likable about her to the baby stuffed in draws most of the day. Which is more relatable to the average reader?

Hi WD,

Ideally, the reader should be able to connect at all times. If you show each of these things with affect and empathy for your character, the reader should be able to connect to the character and care about their passage through these ordeals you describe too.

Best of luck with your book!

So is there no such thing as a book series, that is real life and not fiction? Especially when so many things have happened to the character over an almost 60 year span. Even stories of family members that are bazar in their own way. Should I just write the most important to my character and leave all the other craziness for another book, or try to fit it all in. Sorry last time I will bother you.

Thank you! Great information.

Thank you, Sharon! Thanks for reading.

[…] How to Write a Novella – 6 Essential Tips | Now Novel […]

Very good and practical advice. But one thing needs more clarity. If we resort to heavy editing /trimming, narrative may look artificial, disconnected. Pl elaborate, tks

Hi Syed, thank you for your feedback and or sharing what requires further clarification. To be honest, if that is the result, then it is ‘bad’ editing, as editing should create more cohesion, more clarity. If you mean cutting (e.g. taking passages out to turn a novel-length story into a novella), I would suggest rather structuring a story for a shorter format from the start as making such large cuts later is indeed challenging (and it would be a more economical use of time to aim for novella length from the start of a project).

I hope this answers your question!

this is so helpful, thank you.

Hi Laura, so glad to hear that. Thank you for reading our blog and sharing your feedback.