Clarity in writing means the ease with which a reader can understand you. It means avoiding unintended ambiguity or confusing sentence structure. Read 7 tips for keeping writing clear and engaging:

What is clarity in writing?

Clarity in writing refers to writing’s ability to convey:

- Coherent, intelligible meaning. Readers can understand the writing and what the author is trying to say, to a reasonable degree

- Sharpness of image or idea. If you think of a diamond, clarity allows light to refract better. It makes a stone more dazzling and its shape clearer – the same goes for clarity’s polishing effect on writing

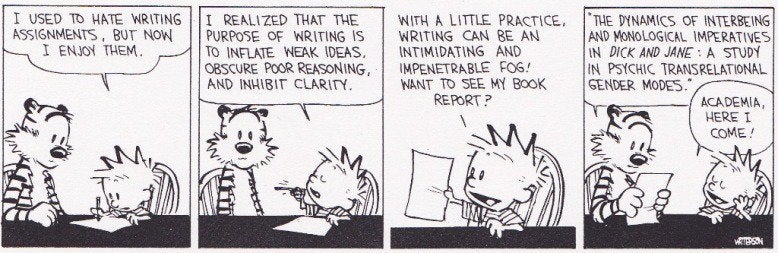

As Bill Waterson shows using irony (while satirizing obscurity in academic writing), clear writing is not:

- Intimidating in style (even if complex)

- Impenetrable/almost impossible to understand

- A fog of words designed to obscure weak arguments or threadbare meaning beneath

The purpose of writing is to inflate weak ideas, obscure pure reasoning, and inhibit clarity. With a little practice, writing can be an intimidating and impenetrable fog!

Bill Waterson in Homicidal Psycho Jungle Cat, 1994.

So how can you keep it lucid, ensure clarity in writing?

1. Know language rules by heart

Grammar may seem dry and boring. Knowing how language works is crucial to using it well, though.

The clearer your understanding of ‘the rules’, the more leeway you have to break them creatively. You break language rules on purpose, rather than by accident.

Get a decent style guide, such as The Elements of Style by Strunk and White, or Oxford’s Essential Guide to Writing. Read it and also toss out what doesn’t work for you or is clearly outdated (after all, even the most sacred texts have needed revisions!)

Great grammar resources from reputable sources such as Oxford’s beginner, intermediate and advanced grammar exercises are available online for free.

2. Practice concision

Concision is a constant and watchful process.

As you edit, ask:

- Did I use ten words to say what I could using three?

- Is there a good reason for this section to be wordier?

Say, for example, you were describing a teacher who is boring and verbose.

Here, characterization might override the benefits of clarity and concision. The teacher’s expressive style might not be ‘good’ style, and you want to depict that.

You might want the character to have a wordy voice, to sound like Calvin’s description of his paper’s title in the comic strip above.

Lack of concision or clarity, in other words, may be an intentional, stylistic choice, too.

Yet you could also summarize a character’s wordy rambling in another character’s words (for concision’s sake). For example, a student-narrator might say:

He droned on for thirty minutes, using words like ‘profligate’ and ‘irascible’ until all you could hear throughout the classroom was the flutter of dictionaries’ pages.

Clarity in writing: Exercise – Rewriting

Open a novel. Flip through to a random paragraph.

Read it through carefully, then try to rewrite it with the same overarching meaning. Try to do this in only two sentences.

What can be cut/condensed without losing much meaning?

3. Check common ambiguity causes

Clarity in writing suffers when your reader struggles to understand what information applies to which noun.

Common sources of clarity-reducing ambiguity in fiction include:

- Poorly structured sentences with ambiguous modifying clauses (more on this below).

- Dangling participles (more on this below, too).

- Missing words, dialogue attribution and other omissions.

See this guide to fifty-two common errors for common mistakes (some of which cause unintended hilarity).

Let’s explore further:

The snake did what!? Writing clarity and modifying clauses

A modifying clause tells us more about another word in a sentence.

For example, an introductory phrase that tells us the way something or someone moves:

Whistling and cycling through the forest …

If we were describing a girl whistling while she cycles through a forest, this would be an incorrect or dangling modifier:

Whistling and cycling through the forest, the snake made the girl scream.

We read ‘the snake’ as the subject doing the whistling and cycling (though context tells us the girl’s performing the action). A talented and rare specimen, indeed!

Correct (and clear):

Whistling as she cycled through the forest, the girl screamed when she saw the snake.

You can avoid ambiguity with modifying clauses by:

- placing the subject described by a modifying clause (the girl in the example above) immediately after the clause

- Rewriting the sentence, placing the subject at the start of the action, e.g., ‘The girl was whistling and cycling through the forest when she saw a snake and screamed’

Dangling participles (you can’t sentence a sentence)

Dangling participles are another type of clarity-fogger.

This is when the noun that a participle phrase applies to is left out of a sentence.

For example:

If found guilty, the sentence will be the maximum of twenty years.

Here, the phrase ‘if found guilty’ lacks the noun it refers to. It seems ‘the sentence’ itself is under trial.

Clearer (due to the main noun’s inclusion):

If the defendant is found guilty, his sentence will be the maximum of twenty years.

These are just two types of ambiguity that creep into even strong writing easily.

Fix these and other errors by hiring a good editor.

4. Read passages aloud

Reading passages of your own writing aloud is a useful exercise for many reasons.

It’s a great way to catch weak dialogue where it should flow and feel like real speech.

If you read over a paragraph and it seems unclear, read it out aloud. Where do you stumble? Where have you not given the human voice sufficient rest?

Shorter sentences and paragraphs are useful for maintaining good clarity and pace, while varying length adds interesting rhythm.

5. Be specific

Specificity is the enemy of word-fog. Describe this specific detail, that cut and gleaming facet.

A quote by the great Anton Chekhov we discussed in our monthly webinar suggests why specificity lends clarity:

Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.

Anton Chekhov, quoted here.

An image like the broken glass glinting under moonlight in Chekhov’s example helps clarity because it:

- Shares specific, detailed information that is easy to picture and understand

- Privileges concrete imagery over abstract example

Writing exercise: Clarity in writing – becoming Chekhov

Write two brief, two-line descriptions, each describing a specific sight that tells the reader ‘the moon was shining’.

Bonus: Like Chekhov’s broken glass, the imagery suggests something suspenseful or intriguing has occurred or will soon happen.

6. Simplify and connect

Coherent, clear writing requires a balance of simplicity and connection.

Say, for example, a snake is pedaling a bike through a forest (in a children’s story where animals defy the limits of their usual anatomy).

Say we use a simile (a comparison using ‘like’ or ‘as’) to describe the snake:

He pedaled hard as he whistled. The sound was serpentine, like wind blown across the mouth of the smallest glass bottle.

Next, we add another simile:

He pedaled hard as he whistled. The sound was serpentine, like wind blown across the mouth of the smallest glass bottle. It sounded like a thousand tiny flutes playing in a cave.

The extended metaphor mixes imagery, from someone blowing across a bottle to flutes in a cave.

The more the writer chops up and mixes unlike things, the harder it becomes to follow their logic. We lose track of where we are.

Simplify where it makes sense to. Draw similes and metaphors from the same neighborhood of images and ideas, for clarity’s sake.

7. Write drunk, edit sober

‘Write drunk, edit sober’ is a quote often misattributed to Ernest Hemingway. It implies that writing requires a degree of abandon, while editing requires precision and focus.

Whoever first said it, it catches two important aspects of clarity in writing. Namely:

- Clarity is not a first draft concern: First drafts are sloppy, patchy (‘drunk’, more often than not).

- Clarity takes focused, attentive work: Editing isn’t fast or consistently thrilling, but it is vital. What words should be capitalized? Is X a proper or common noun? Even seasoned editors may have to look up the finer details often.

Stopping to fiddle with words constantly may lead to the opposite of clarity in writing. Writing that feels overly fussy. Writing with the life squeezed out of it. Working loose and light has its own advantages.

Give yourself freedom to make mistakes. Let snakes be; let them whistle and win the Tour de France. Then get a good editor.

6 replies on “Clarity in writing: 7 musts for lucid prose”

WRITING IS MIRROR OF OUR MIND.

That’s an interesting thought, Midathala. Jorge Luis Borges said all writing is autobiography.

This article is going to be so helpful for me when I do my first revision. Thank you for including it in your blog.

I’m glad to hear that, GJ! Good luck with your first revision and have fun with it. Thank you for reading our blog.

Love your blob. Always very supportive and informativ content. A gem!

Thanks for reading our ‘blob’, Max! We’re glad you’re enjoying it.