World building tips often focus on fantastical genres such as fantasy and sci-fi, because they involve creating worlds different to our own. It’s important to create immersive, interesting and believable settings, whatever your genre. To build a detailed world, one to rival Westeros, Hogwarts (or Dickens’ London), use these world building tips:

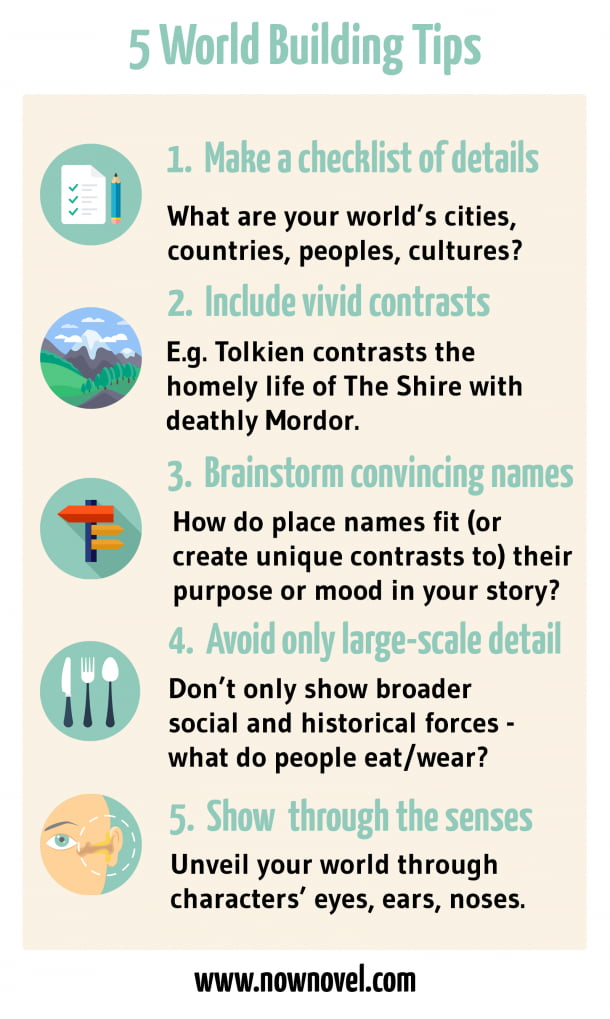

Five world building tips:

- Create a summary of crucial world building details

- Give your fictional world vivid contrasts

- Brainstorm convincing names for your world’s locations

- Avoid focusing only on large-scale details

- Use the senses to show your world through characters’ eyes

Let’s unpack these ideas further:

Create a summary of crucial world building details

Famous fantasy authors’ worlds are widely adored because there is detail and specificity that makes them feel real.

Film-makers have an easier task of bringing places like Tolkien’s Mordor and Rowling’s Hogwarts School to life thanks to their creators’ rich description and imagination.

Legions of younger and older readers fell in love with Rowling’s Hogwarts, for example, because they could imagine her setting to its borders. From the castle’s dining hall with its long tables and floating candles to its outer, more dangerous limits. The nearby ‘Forbidden Forest’, for example, or the menacing vegetation and grounds where characters fear the wild, flailing tree Rowling names the ‘Whomping Willow’.

Great fictional worlds, like this one, have contrasts, details, atmospheres. The vaults of Rowling’s crypt-like bank, Gringotts, for example, have a different tone and mood to her student-filled castle.

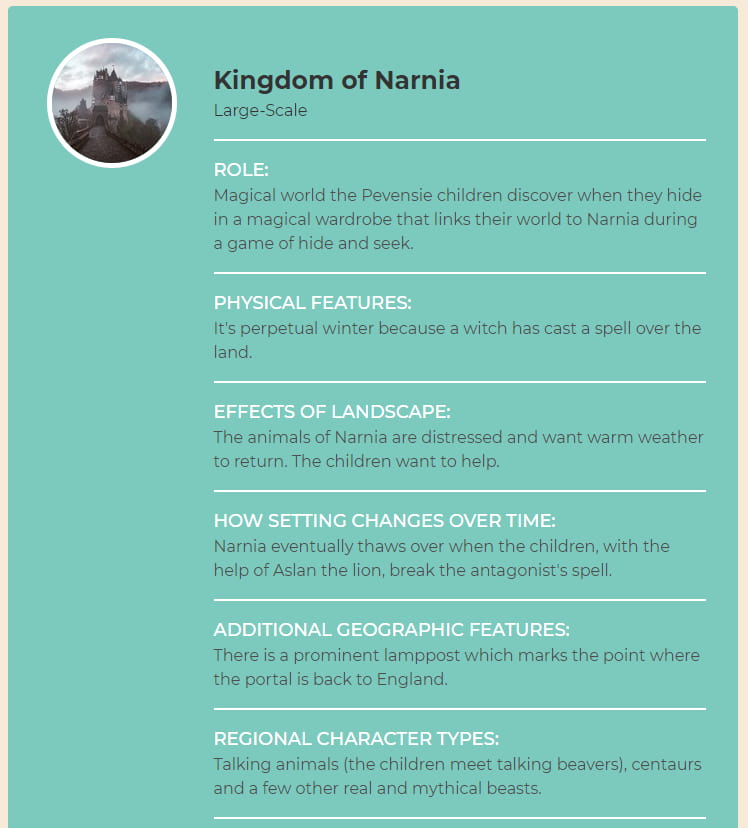

Create a summary of details you want to include in your novel’s world. Whether you’re evoking a magical setting like Hogwarts or a real one like modern-day Paris, this will create the scope of your setting.

Think about:

- Your setting’s role: Where will your story’s key action happen? (E.g. a central character’s home or CIA headquarters)

- Broader macro locations: What cities, countries, or even continents or planets might your story span?

- Names and features of towns or cities: What identifies and distinguishes one place in your world from another? In Harry Potter, Harry’s mean aunt and uncle’s house is a dreary, typical suburban home, with strict rules. Hogwarts School has its own strict rules, but by contrast is more magical, exciting and perilous

- The peoples/demographics that inhabit your world (is everyone human? Are there tensions between groups? If yes, why?)

- The social and cultural features of your world (for example, Rowling gives her wizard community shared sporting events (The Quidditch World Cup) and other shared cultural and social landmarks

Give your fictional world vivid contrasts

World building tips often stick to making your world believable. Yet believable is not the same as uniform.

Every world (including our own) has surprising differences from place to place. There are many cities where rich and poor live in radically different circumstances, separated by only a highway, for example. Asking world building questions such as how geography differs from place to place will help you find the contrasts and the similarities between settings.

Think about the contrasts you might create in your fictional world. What contrasts would serve your story? Imagine a novel about a young girl who fights an authoritarian government, for example. The side of the highway she comes from will determine, to some extent, what tools she has to arm her resistance. Setting shapes our backstories.

Tolkien’s Middle-earth gives us many examples of how effective contrast is in world building. The Hobbits’ homeland, the Shire, is a world of local homeliness. Compare this to Tolkien’s un-homely Mordor, the villain’s base. Here, sulfurous pits and jagged peaks threaten travelers.

The contrasts in Tolkien’s world create additional obstacles for characters. The closer they get to Mordor’s corrupt heartland, the more corruptible members of Frodo and Gandalf’s party become, too, resulting in small betrayals. Setting actively shapes characters’ behaviour along with tone and mood.

Contrasting zones in world building is thus useful, whatever your genre. In a romance novel, for example, lovers on an exotic vacation might find an idyllic world that helps them bond, away from the city’s chaos. Alternatively, they might have a holiday from hell. Neither speaks the local language, and everything goes wrong.

As you build your world, think how you can make your settings active players in characters’ options, choices, goals and fears.

Brainstorm Detailed Settings

Brainstorm detailed settings for your world in Now Novel’s outlining tools and add images to inspire you as you write.

Brainstorm convincing names for your world’s settings

A great name conveys the mood of a place. Tolkien’s world is full of names that convey the tone and mood of the places they describe. ‘The Shire’ has a soft assonance, fitting a world of green pastures. It has echoes of ‘Ireland’ or many a British rural town.

Mordor, by contrast, is guttural sounding, using Germanic or Norse-sounding roots. It fits this setting’s more Gothic, somber mood.

The fantasy novels of Sir Terry Pratchett yield great examples of compelling place names. For example, ‘Discworld’. This name literally describes a core physical feature. It resembles the ‘flat Earth’ people once thought Earth itself was.

Discworld is also balanced on the backs of four elephants which in turn stand on the back of a giant turtle, the Great A’Tuin. Thus Pratchett gives a literal name to a setting that is absurd and imaginative, so there is contrast between the simplicity of the name and the complexity of its features. It’s this combining of the mundane and literal with the wildly imaginative that gives many of Pratchett’s novels their sly, dry, satirical humour.

When you brainstorm names for places in your world building, think about:

- Purpose: What is purpose of this setting? For example, Rowling calls the magical London high street in the Harry Potter books ‘Diagon Alley’. This echoes with ‘diagonally’. It’s a good name for a street that exists just slant to our world, just beyond our non-magical awareness.

- Mood: What is your place’s mood? Think about the Tolkien examples above and how the sounds of the words themselves feel apt for the place.

Avoid focusing only on large-scale details

Part of why we focused on creating mid-scale and small-scale setting too in the Now Novel World Builder tool is that detail is an important element of setting. What does a character’s home look and smell like? What is this street like in the morning? And at night?

Create a sense of the broader social and historical forces at work in your story, but don’t neglect the details that give us a sensory feeling of place.

Remember to include small-scale details about your world and its ways, where relevant to the story. Think about what characters in the different locations of your story wear and eat. How do their speech patterns, slang, or cultural customs differ? A naval town, for example, will likely feature fresh seafood strongly on the menu.

It’s small details like these that reveal a world so that we the reader say ‘that makes complete sense’ (or ‘Wow, that’s surprising!’).

5: Use the senses to show your world through characters’ eyes

One way to bring your fictional world to life is to use sense description. Simply describing what a character sees, to start with, can bring a larger setting to life.

Take, for example, David Mitchell’s protagonist Eiji Miyake, in his 2001 novel Number9dream. The character is a boy who comes to Tokyo to search for his father. Here, Mitchell’s protagonist describes the view from a local Cafe, and the broader Tokyo cityscape:

‘Tokyo is so up close you cannot always see it. No distances. Everything is over your head – dentists, kindergartens, dance studios. Even the roads and walkways are up on murky stilts. Venice with the water drained away.’

The description effectively shows us defining features of the inner city – it’s closeness, claustrophobia and height. This sense of multiple levels is also important for Mitchell’s world building. We will later see his protagonist stumble across different levels in the city, from the ‘above ground’ world of love interests and missing fathers to the dangerous mob-ridden underworld of Tokyo that Eiji is eventually drawn into on his quest.

Later, Mitchell uses other senses – sound, smell – to deepen his world. Here, for example, he describes the same scene after a typhoon:

‘One hour later and the Kita Street/Omekaido Avenue intersection is a churning confluence of lawless rivers. The rain is incredible. Even on Yakushima, we never get rain this heavy. The holiday atmosphere has died, and the customers are doom-laden… Outside […] a family of six huddles on a taxi roof. A baby wails and will not shut up.’

As Mitchell progresses through the story, he paints a clear sense of his character’s world by describing its changing moods, atmospheres, and weathers.

Create a more compelling world for your novel. Use ‘Core Setting’ and the Word Builder in the story dashboard to brainstorm and connect, and create a breathtaking sense of place.

13 replies on “World building tips: Writing engaging settings”

This is extremely helpful, suggesting how to focus on the detail without getting bogged down in it but also how to look at the broader picture without losing one’s way has been made much clearer for me. The examples you use to illustrate your point are just right. Many thanks.

Thanks so much, Karen. Thrilled you found these suggestions helpful.

These are great tips, especially the small details that show the story takes place in a different world. A lot of S.F. & Fantasy books tend to lapse back into the Naturalist style of writing, giving page long descriptions of everything. I find that this type of description, at least for me, really only delays the story and is really too much information.

I am currently working on a fictional city in a fictional nation that takes place in what is basically our reality and time. But, even when I was working on my fantasy epic, I would only put in such details about the world that my characters interacted with, or details that were new to them, so the reader can see them through the characters’ eyes.

On a different note, I look at a lot of different writing sites, but this is my favorite one. You seem to be the only site I’ve found that will mention literary fiction. (Some of my favorite writers: Graham Green, Umberto Eco, Italo Calvino, Hermann Broch, &ct.) Keep up the good work.

Hi Mcrumph – Great taste, I love Italo Calvino myself! Have you read his book ‘Invisible Cities’? Some really imaginative world building in there (in miniature). And very whimsical on the whole. I hope your story is coming along well! You’re right that ‘necessary’ description is often best, to not weigh down the narrative. Just because you’ve brainstormed part of a setting doesn’t mean you have to include it, sometimes it’s just for you and your imagination 🙂

These tips are so useful! I will tell my friends about your website. Thank you! I am very grateful for this post.

Thanks for telling your friends about us, Kay. I’m glad you found this post helpful 🙂

What a useful tips! I loved the post, very helpful. Thank you.

Thank you, Una beta. Thanks for reading our blog!

Terrific suggestions coming through!

Thank you for this kind feedback, LT. Thank you for reading our blog!

[…] blogs, this tip is for you. Once again, the Internet has lovingly bestowed lists of potential worldbuilding questions that help build your universe with each […]

Dark and light, desolate and uplifting very thought provoking!

Thanks so much Hazel. I’m so pleased that you found it useful. There’s some fascinating information in this blog post on how to build a detailed world. For example:

Create a summary of crucial world building details

Give your fictional world vivid contrasts

Brainstorm convincing names for your world’s locations

Avoid focusing only on large-scale details

Use the senses to show your world through characters’ eyes