Introducing and describing characters are key parts of the storytelling process. Read 6 tips for describing characters using direct characterization, with examples:

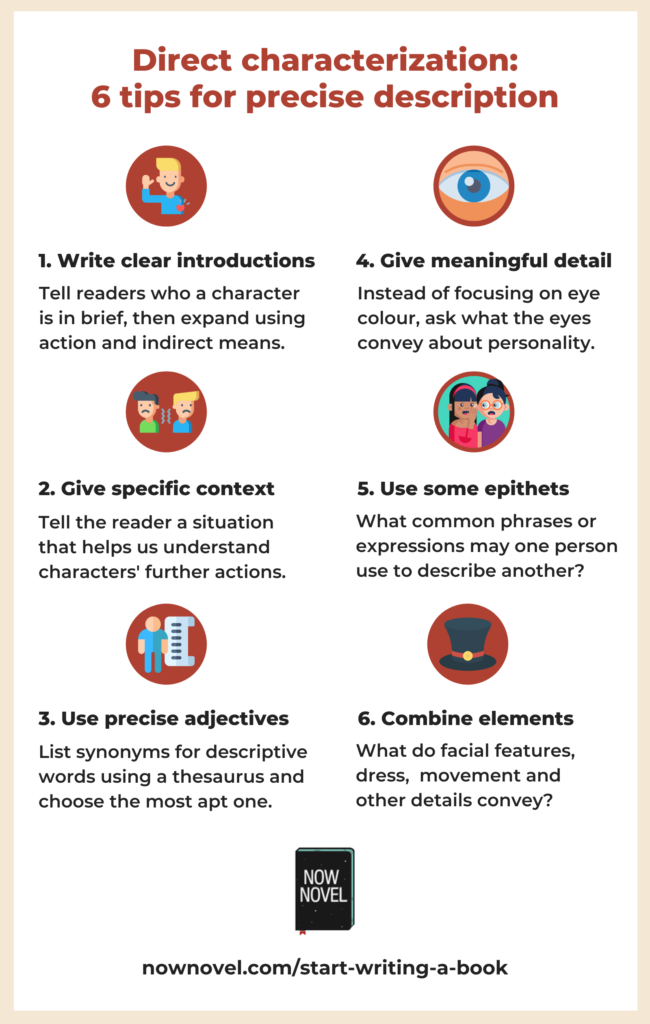

Tips for direct charactization:

- Write clear and concise introductions

- Give specific context

- Use precise adjectives

- Give meaningful details

- Use occasional epithets or phrases

- Combine multiple descriptive elements

First: What is direct characterization?

Put simply, direct characterization tells while indirect characterization shows.

Direct characterization describes characters by stating their feelings, world-views, personalities, conditions or situations.

Indirect characterization shows a character’s personality, mood or situation by inferring rather than being explicit.

Direct vs Indirect characterization: Two examples

Direct characterization: ‘The only thing that made him a conman was that he’d conned himself into believing he had a hope in hell of stealing the Van Gogh.’ This tells us explicitly about the character’s flaw, his delusion about his thieving ability.

Indirect characterization: ‘He felt all around the window with ungloved hands. Gloves are for amateurs, he thought, while leaving a mess of fingerprints. He landed on the gallery floor with a heavy thud. Immediately an alarm rang out.’ This shows us the thief’s persona through his thoughts, actions and choices, without explicitly saying what a bad thief he makes. We can deduce that much.

Let’s explore direct characterization examples and tips:

6 Tips for direct characterization

1. Write clear and concise introductions

Direct characterization often introduces, while indirect characterization substantiates.

In other words, a first line in a scene might tell us who a character is, explicitly. Following lines show us actions, thoughts, movements, dialogue, that further substantiate a statement such as ‘She was an angry woman.’

Take this example, the opening of the first chapter in Kent Haruf’s Eventide:

They came up from the horse barn in the slanted light of early morning. The McPheron brothers, Harold and Raymond. Old men approaching an old house at the end of summer.

Kent Haruf, Eventide (2004), p. 3

Here Haruf introduces the aging McPheron brothers in simple, explicit description. He tells us plainly that they are old. Key facts about them – e.g. the rural setting implied by a horse barn – are mixed in with simple telling.

Another example of direct characterization that introduces characters swiftly:

Everything had gone wrong in the Oblonsky household. The wife had found out about her husband’s relationship with their former French governess and had announced that she could not go on living in the same house with him. This state of affairs had already continued for three days and was having a distressing effect on the couple themselves, on all the members of the family, and on the domestics.

Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina (1954), trans. Rosemary Edmonds, p. 5

Tolstoy’s narration plainly explains the situation (marital infidelity) and the effect it has on Stiva Oblonksy’s wife and their household.

Effective direct characterization thus may introduce:

- Key facts about characters (where they live, their age, their current emotional state or situation)

- Context for further indirect characterization: When we later see Stiva, the cheating husband, sleeping on a couch in his study, we know why

2. Give specific context

Leo Tolstoy’s example of direct characterization above is an example of how direct characterization supplies immediate context.

Because we know Stiva is a philanderer, and have been told how angry his wife is, we have context for his next actions (sleeping on a couch in his study).

Context is crucial in storytelling. Without understanding a character’s situation now or their backstory, we can’t understand why they make the choices they do. We don’t know what options they have, or where they’re heading next.

Context you can supply through direct characterization includes:

- A character’s dominant traits (e.g. whether they’re mostly optimistic or pessimistic, happy, melancholic or neutral, uptight or easygoing, etc.)

- A characters feelings, desires or motivations (i.e. stating directly what a character feels or wants)

- Basic ‘ID’ facts about a character (their age, gender identity, relationship status, appearance, and anything else that may supply context for what will happen during their story)

Here’s an example of direct characterization from Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible:

We came from Bethlehem, Georgia, bearing Betty Crocker cake mixes into the jungle. My sisters and I were all counting on having one birthday apiece during our twelve-month mission.

Barbara Kingsolver, The Poisonwood Bible (1998), p. 5

This direct characterization gives us immediate context. We know:

- We’re reading about a family from the USA entering an unfamiliar setting (‘the jungle’)

- There is a group of sisters

- The sisters want to still enjoy the comforts of home in a new environment (birthday cake and celebrations)

The context supplied suggests the girls’ privilege, as well as the unknown element of their home for the next twelve months. Their wish to celebrate their birthdays clearly shows their attachment to their lives before their present situation.

This direct characterization creates a sense of the girls’ wide-eyed naivety and their determination to maintain their own traditions.

3. Use precise adjectives

In indirect characterization, you might show a character is old via their thoughts. For example: ‘I remember way back in 1920s how we used to curl our hair’.

In direct characterization, you could state a character’s age using an adjective, as Haruf does when he simply calls the McPheron brothers ‘old’ in the above example.

When writing direct characterization, try to find an adjective or synonym for a more common describing word that fits the paragraph. For example:

To teenage Joseph, the couple looked ancient; antediluvian (had they been on the ark?) yet the woman’s face lit up like a young girl’s when she passed him a toffee with a sly wink.

Here, the word ‘antediluvian’ (meaning ‘belonging to the times before the biblical flood) works well for describing the couple, as it’s paired with Joseph imagining they might have been aboard Noah’s Ark.

Keep a good thesaurus or use a website such as thesaurus.com. When choosing an adjective (for example, ‘young’) see if there isn’t something that fits the situation more descriptively, such as:

- budding

- green

- youthful

- fledgling

- puerile [for negative connotations of immaturity]

[Brainstorm character description and develop your story using our easy, step-by-step outlining tools.]

4. Give meaningful details

Writing a succinct, specific description that captures a character’s personality is hard. It’s easy to focus on details that don’t tell us much, such as a character’s eye colour.

Remember to show your reader what is interesting or meaningful about a character in description.

For example, instead of ‘she had blue eyes’, could this description do more work introducing the character?

For example:

- ‘She had blue eyes – a pale, rare blue that made her gaunt face appear almost supernatural, more ethereal’

- ‘His blue eyes had a light, lively intelligence behind them’

In the first example, describing a character’s eye colour leads us into more facial details that begin to create a more specific, direct mood.

In the second example, eye colour leads to the ways the eye area suggests a person’s personality.

5. Use occasional epithets or phrases

Direct characterization is useful for creating an impression of a character via another’s words.

For example, a character may use an epithet (a characterizing word or phrase) to describe another.

Take, for example, the epithet ‘dirty’. If a character describes another as a ‘dirty old man’, this suggests a lewd nature. He may be the type to make lewd, inappropriate, harassing comments.

Think of common epithets and phrases people might use to describe others, for example:

- ‘The lights are on but no-one’s home’ (suggesting a vacant/dumb nature)

- ‘They’re a real jack of all trades’ (suggesting a person dabbles in things without developing true skill)

Epithets offer a creative, metaphorical way to give direct characterization.

6. Combine multiple descriptive elements

Successful direct characterization combines multiple descriptive elements to create a full, vivid image.

A classic example of direct characterization is Charles Dickens’ brilliant characterization of Pip’s mean sister in Great Expectations:

My sister, Mrs. Joe, with black hair and eyes, had such a prevailing redness of skin that I sometimes used to wonder whether it was possible she washed herself with a nutmeg-grater instead of soap. She was tall and bony, and almost always wore a coarse apron, fastened over her figure behind with two loops, and having a square impregnable bib in front, that was stuck full of pins and needles. She made it a powerful merit in herself, and a strong reproach against Joe, that she wore this apron so much.

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations (1861), full text available here.

Dickens combines the irritation of Pip’s sister’s skin (how it looks like she washes with a grater) with details of dress (her apron ‘stuck full of pins and needles’ and the disgruntled way she wears it) to create the impression of a flustered, grumpy person. Mrs. Joe’s description is full of prickliness, from the image of the grater to the pins and needles.

Need help developing memorable characters? Use the ‘Characters’ section in the Now Novel dashboard to create detailed character profiles and develop your story.