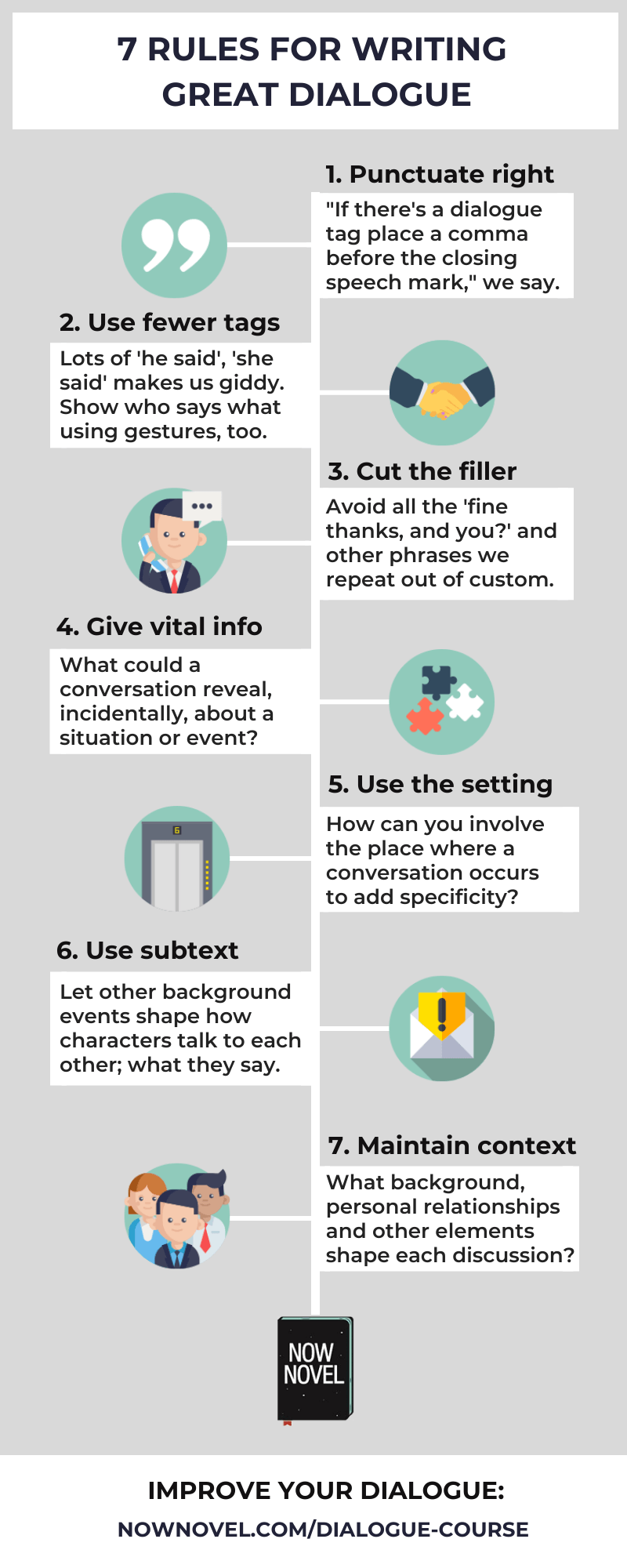

Dialogue rules aren’t set in stone but help us create believable characters who have distinct, memorable voices. The best dialogue gives insights into characters and their motivations. Getting dialogue punctuation right is important, as is keeping dialogue entertaining. Here are 7 dialogue rules for writing conversations worthy of eavesdropping:

1: Learn dialogue rules for good punctuation

Before you can write conversations that bristle with tension or brim with excitement, you need to master the rules for punctuating dialogue. [Below is a brief guide but our 4-week course covers much more. At the end, you’ll submit a piece of dialogue incorporating what you’ve learned for professional critique. Learn more.]

Rule 1: Remember to open and close speech marks to set dialogue apart from surrounding narration.

At the end of a line of dialogue, if you use a dialogue tag, remember to use a comma before ‘he said’ or ‘she said’ instead of a full stop. The tag is still part of the same sentence. This is a mistake we often see in beginner authors’ critique submissions on Now Novel. An example of good dialogue punctuation:

“I wish you would use a comma and not a full stop before your dialogue tag,” she grumbled.

The second rule: If a character’s speech is interrupted by a dialogue tag or action, close and re-open speech marks.

Commas before the dialogue tag always go inside the quoted speech, just before the closing quotation mark. Here’s an example:

“I wish you would stop interrupting,” she said, holding up her palm, “and let me finish!”

The third rule: Always start a new paragraph when a different character starts speaking. This way it’s clear who says what in a scene involving two or more characters.

“I wasn’t interr-“

“There you go again.” She glared.

The fourth rule: If one character speaks over multiple paragraphs, only close quotation marks at the end of the final paragraph.

This is used when a character has a long monologue, such as when retelling an event or story. This prevents the reader from erroneously thinking a new character has started talking. An example:

“There you go again.” She glared. “As I was saying, I’ve told you the rules of dialogue before but you keep forgetting.

“Where was I? I can see from your face you think I’m being unnecessarily hars- no, don’t interrupt again.”

2: Keep dialogue tags to a minimum

As a rule, if you can establish who is speaking and how they are speaking without dialogue tags, avoid them. Compare the following:

“I thought you said you were arriving a four,” he said angrily, his face thunderous.

And:

He stood scowling, his arms crossed. “I thought you said you were arriving at four?”

Because the character action (the character stands in a posture suggestive of anger or frustration) precedes the dialogue, you don’t need to attribute the words in the second example. It’s clear the man with folded arms says the cross, rebuking words. Gesture, action and body language mid-dialogue supplies subtext, implied meaning.

Where possible, minimize dialogue tags using body language and gesture instead. This helps us to hear a character mid-conversation and see them too. This is one way to make dialogue more vivid.

3: Cut out filler words that make dialogue too lifelike

You might be thinking, ‘Hold on, surely dialogue should be lifelike?’ Dialogue in a story differs from real-world conversation, though.

In real life we repeat ourselves sometimes. We exchange pleasantries before we get to the real core of what we want to talk about. In writing fiction, you can get to the crux of a great conversation faster. Filler words may be true to life, but don’t bore the reader.

The difference between dialogue in life and dialogue in stories is that in stories, you need to cut day-to-day conversation that is extraneous or irrelevant. Even if you are showing a romantic duo engaged in an intimate, ordinary moment, let your characters’ personalities, fears, motivations and desires come through in their words.

For example, a bland everyday scene could run as follows:

I heard the key in the front door. It was him. “Hi, love. How was your day?”

“Good thanks and yours?”

“It was fine thank you,” I reply.

Instead, something more interesting could proceed as follows:

I heard the key turn in the front door. He stomped in and threw his bag down.

“Bad day, huh?”

He shrugged, grimacing while making a beeline for the kitchen. “It was fine,” came his voice, sounding too measured. Something was clearly up.

In the latter example, there’s immediately a sense of story. Surrounding the dialogue are actions (the throwing down of the bag and the anxious worrying of the viewpoint character) that make the dialogue pregnant with a sense of event.

Cut out filler words and instead focus on finding the emotional core of each conversation in your story. What does it show about your characters and their circumstances?

The above example could show that the viewpoint character is anxious and confused because her significant other is failing to communicate something bothering him. Most importantly, it shows us that there is a revelation of some kind in waiting – it drives the story forwards by making us ask, ‘what happened?’ and ‘what will happen next?’

4: Give readers vital story information through dialogue

Good dialogue consists of engaging or illuminating conversations. It often helps us understand characters’ strengths and limitations, goals and obstacles.

Beginning writers who aren’t practiced with writing conversations often create exchanges that make the story meander rather than get to a destination.

When you write any piece of dialogue, write down answers to the following questions before you start:

- What do I want my dialogue to tell readers about my characters’ personalities?

- How will my dialogue to tell readers about my characters’ present situation?

- What future expectations or questions will the reader have about the story’s plot because of this conversation?

Asking questions about your dialogue will help you learn how to write good dialogue. Purposeful dialogue that adds depth to characters while entertaining will keep readers interested.

5: Show characters’ surrounds while they talk

Remember that tone and mood are essential components of a story. If your characters seem to speak in a vacuum, their exchanges will feel dry and bland.

If your characters are meeting in a restaurant, for example, use this setting to your advantage. Perhaps service staff could interrupt to take their order at a key point, when you are just about to release a vital piece of information answering a question the reader has been harbouring. This device would help create a more suspenseful mood. Involve readers in the emotional crux of your scene by bringing your characters’ surroundings into their conversation.

6: Don’t always make characters say exactly what they feel

If you think about real people, everyone tells little lies from time to time. We might feel awful and walk into a social occasion with a broad grin, not wanting to dampen the mood. There are hundreds of ways to say ‘I feel terrible’, including ‘I feel great’ – it’s the way you say things that matters.

Making a character’s words at odds with their body language can be effective for characterizing your novel’s cast. A character might have a motivation for not showing any vulnerability in a situation, and thus might grin and be outwardly jovial. You can show the chinks in their armour using body language and small actions, such as fidgeting. This is why it is important to not only use characters’ voices and words but their bodies and movements in dialogue too.

7: Remember context in dialogue (the reason for the conversation)

To make your dialogue interesting, remember that fantastic dialogue lets us see the ‘why’ behind it. Dialogue involves context (and infers subtext).

Two romantic leads might fight over doing chores, or what to do over their weekend. Yet the dialogue should tap into the underlying subtext. Why this fight, and why at this moment in the story? Perhaps one character has realised the other does not fulfill them on a fundamental level.

Think about dialogue at multiple scales: Think about what’s going on immediately in this scene, right now. Yet also think about where its roots lie in prior actions and scenes and how your characters’ words can reveal glimpses of these roots to the reader or viewer.

Which authors do you think write the most fantastic dialogue?

Read our tips on creating natural and realistic dialogue.

Get feedback on your dialogue in our critique community, or one-on-one feedback and guidance from an experienced editor.

28 replies on “7 dialogue rules for writing fantastic conversations”

Good post. I was rewriting the first chapter (can’t remember the editing that was done) and since I lost all that was edited (used some horrendous app called Scrivener) I thought that I may start with a dialogue, this way I can cut the superfluous and bring some ‘life’ into the picture and draw the reader without bogging them down with descriptions.

Sounds like an excellent plan, Elizabeth. I’m sorry to hear about your Scrivener mishap!

I tried Scrivener too. Whilst I didn’t experience any tragedies like yours I didn’t find it intuitive and felt I spent more of my time trying to get to grips with software too complex for my needs than writing. In the end I went back to Word, and I now use Powerpoint for my planning/plotting – simply a slide per chapter with a few lines of summary and colour coded to indicate character appearances, plot lines and locations. It’s a little more manual but I have complete control and didn’t need to learn anything

Thanks for tne neat idea (I’ll try it) Scrivener is not what it portraits to be. Lot’s of reviewers receive the app for a review and there’s a lot of ‘good’ reviews from people commissioned to write the stuff. Matter of fact, among many others so called good reviews I found one that a programmer turned into writer–scrivener average consumer–stated that after two years he thought he knew scrivener but found out he didn’t. While he thought this was a good review, since scrivener is supposed to be an alitist gadget for the people in the know, his review only tells you of the inneficience of this app.

Scrivener promises the skies but give you hell with all the shock and traumas of the experience. My advise, if you are a writer, stay away, away as much as possible from Scrivener (if for no other reason, an app has control of your files and all it takes is a mischievous or ill intend employee to decided “hey I’m going to wipe out all her stuff’.

Thanks Neil for sharing your idea of using power point with us.

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/6471bed13c5251ba00f34a4ede003830c3f3f04589b37299902ebcbddeac69a6.jpg

Sorry for your “lost”. Its incredible Scrivener did that. I used once, and really don´t like it (to complicate and “no look nice to me”/many distraction to my eyes).

I use «YWrite.5» its free and very intuitive writer´s programm; and it does a back up which is saving in your PC in a separate file ( I used to do an extra copy of that on pc and USB). I been used it for almost 2.5 years and never gave me a problem. I really love it. Its very complete for write scenes and chapters. You can add any note you wanted even pics to “inspiration” your places, characters and items. Have many special windows to create everything you need for your writing work. (including planning/plots).

Use Word/Power Point means jump between windows/programs. I got all in one screen (page) front of me, with just a click. By the way, write in Word can be chaotic when you must to “fund” something in particular, specially if is a long novel. *Mine now have more than 300,000 words*

If you wants gave it a change to this light (weight) but *huge programm check it on this link (www.spacejocks/yWriter.html) *His creator is a programmer and writer!

You can regist or not your account. I didn´t and nothing happens if I dont.

For me, is the best. I dont wants change it ever. And its FREE! too amazing to be so complete, for that I recommend it for anyone I think can be useful.

P.S.: Sorry for my english, is not my mother lenguage.

Great idea to use Powerpoint that way, Neil. I think finding an approach that suits your working style makes complete sense.

Thank you! Great tips!

Thank you Alessandra, it’s a pleasure. Thanks for reading.

Thanks, Bridget for this discussion. Each time I read your post , I have this feeling I am in a school. So much education goes on as I get enlightened because of the wealth of information that you share.It is done with such clarity and in an so interesting manner too.

See how you began with little details such as the rules of punctuating dialogue. I always have to take notes . Your material is so rich. I will use your tips to make my WIP better.

Thank you for the kind words, Ohita. I’m glad you’re finding each post helpful.

Great piece! I can definitely see where I can infuse these suggestions into my piece! Thanks so much.

It’s a pleasure, Morgan! All the best for your work-in-progress.

Fantastic piece. Really enjoyed it. Thank you.

Thank you Ger, glad you enjoyed it.

Terrific article! I appreciate your ideas and tips. Keep writing, Bridget.

Thank you, Shon! Glad you’re enjoying reading them.

Just came to revist the post. Concise and straight to the point. I enjoyed. Thank you.

Thank you, Elizabeth! Glad you enjoyed reading this.

I wrote in spanish, which means, the estructure is different than english. But I´m been very intuitive to write dialogues. (People use to say, that I got my straight on those). I´m so happy fund your advises, because just confirm I been doing good! And I will read all “dialogues” series your wrote. Thanks you so much.

In the following example which you give, I think the question mark at the end is wrong, as no question is actually asked. This crime is commonly committed nowadays. Some may say there is an “implied question”, but I maintain that an “implied question” (even if we accurately deduce it) requires a corresponding “implied question mark” – not a written one!

‘He stood scowling, his arms crossed. “I thought you said you were arriving at four?”’

I think the following is correct –

He stood scowling, his arms crossed. “I thought you said you were arriving at four!”

Hi Ralph,

You raised an interesting grey area. Far from being ‘wrong’, however, or a ‘crime’, an implied question semantically has the inflection of a question, and thus a question mark may be used to draw attention to the fact the speaker is awaiting an answer (that their words are not intended as a statement but form, in fact, a question).

The exclamation mark is also a perfectly valid option, though this too would imply a degree or intensity of force, of indignation, that the author might not necessarily want in this instance.

So in this case, if the author wanted the illocutionary inflection of a question to be clear, they could include a question mark. Whether or not it’s a statement or question is a matter of semantics, and punctuation gives the author the option (e.g. whether choosing a question mark or exclamation mark) to finesse the tone of the statement.

Aside from this, however, in context the example is referring to ways to attribute speech other than using tags, so the issue is maybe moot.

I should add that there are instances where the use of a question mark is not optional in this way, for example if using explicit question words such as ‘How’ or ‘What’ (it would indeed be incorrect to write “How’s your mother.”)

Although you could write “How’s your mother!” as a sort of statement (for example, if a character were impressed/shocked by another character’s mom’s behaviour and their statement were more a colloquial expression of surprise/shock). So again it comes down to authorial intention and whether or not the punctuation involved creates or avoids unintentional ambiguity.

[…] 7 Dialogue Rules for Writing Fantastic Conversations […]

Hi, I know this was years ago but what a great pot – thankyou! Found it really helpful.

Hi Anna, thank you for your kind feedback. We’re glad you found it helpful! Thanks for reading our blog.

*Post!

“Now novel, you just gave me dialogue knowledge,” cliffton commented.

“Clifton, I’m glad we could help,” I say. Thanks for reading our blog! 🙂