Understanding how to create tension in a story is key to writing a gripping, ‘I’ll just read one more page before bed’ read. Here are eight steps to ensure your story has effective narrative tension. Watch the brief video below, then read the article:

1: Create a conflict crucial to your characters

2: Create engaging characters with opposing goals

3: Keep raising the stakes

4: Allow tension to ebb and flow

5: Keep making the reader ask questions

6: Create internal and external conflict

7: Create secondary sources of tension

8: Make the story unfold in a shorter space of time

Let’s briefly look at what a frame narrative is. This is when a story is enclosed within another story – at its simplest, as an example: a sailor sitting around a fire with his mates, telling the tale of something that happened in his youth, the frame, so we have the main frame of the present, an outer story, and the youthful tale within that. This literary technique is also known as a frame story, a main story is presented within the context of another story.

Frames can also take the shape of a prologue, the main story, and an epilogue.

Examples of novels that use this are Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353) and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Frankenstein by Mary Shelley is another example. The novel is presented as a series of letters written by an explorer named Robert Walton to his sister. Within these letters, Victor Frankenstein tells his own story, and the creature’s narrative is also included.

In Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë the primary narrative is framed by the character Mr. Lockwood, who rents Thrushcross Grange and hears the story of Heathcliff and Catherine from the housekeeper, Nelly Dean.

A more contemporary example is that Life of Pi by Yann Martel. The novel is framed as a narrative being told by Pi Patel to a Canadian novelist. Pi’s main story involves his survival at sea with a Bengal tiger named Richard Parker.

1. Create a conflict crucial to your characters

When planning your story’s main conflicts, choose a central conflict (also known as a primary conflict) that matters. What is your main character’s first goal? What tension or friction could stand in their way? There are two types of conflict: external or internal conflict.

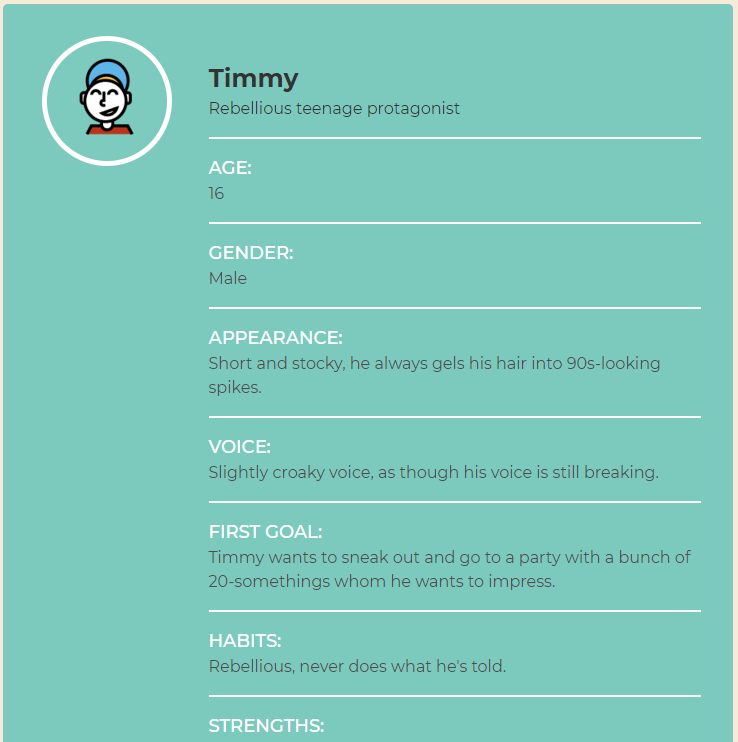

For example, you might have a teenage rebel protagonist who wants to stay out later than their curfew and get up to no good with their friends. A likely conflict would be a disagreement with their parents, and consequences that thwart some of their further goals.

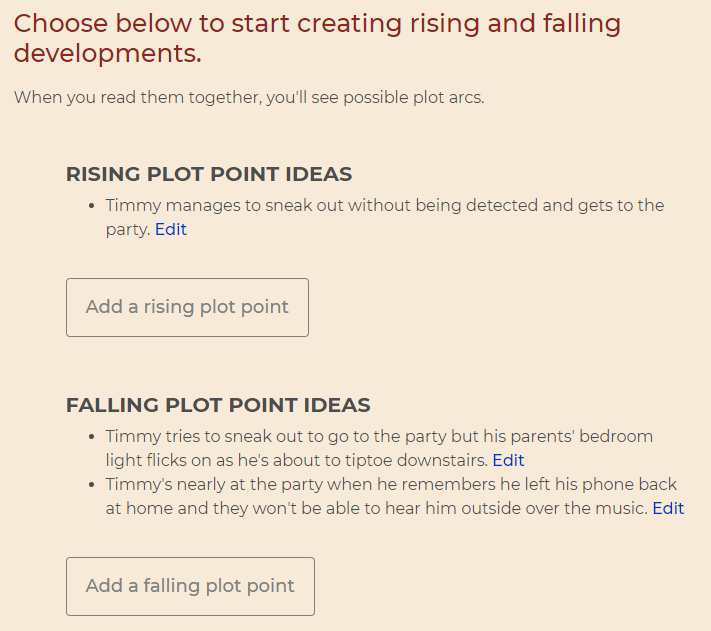

Conflict can be as small as an internal struggle or a relationship between two people breaking down. Or it can be an external conflict as large as the fate of the entire universe. The key is that the conflict has to relate to and threaten the most important things to your characters. Work out your characters’ first goals and the rising and falling action that stands between them and what they want using the ‘Character’ and ‘Core Plot’ parts of Now Novel’s story outlining tool.

2. Create engaging characters with opposing goals

Your readers need to care what happens to your characters, and in order to make your readers care, you need to first engage them. Many writers feel that they need to write characters who are likable, and this is certainly the best way to guarantee reader identification.

However, characters we don’t relate to all the time (or even don’t relate to any of the time) are often equally intriguing. You can still create that emotional investment on the part of the reader, caring about a character by making them interesting and engaging in some way.

One way to make characters engaging is to give them opposing goals, views and other features. Rebel Timmy (the character profile example above) might have a mom who is a moralizing prude, and a dad who’s laid back and doesn’t believe in disciplining his kids. This triangle could create an interesting, tense character dynamic between the three. What’s more, different readers will identify more with different characters in this family setup.

The key here is that characters’ personalities and approaches to conflict can differ and create disagreements, even fireworks.

It’s also important to note that as opposed to real life, it’s better if your protagonist doesn’t get their needs met all at once. This is another way of keeping readers on the edge of their seats.

Create engaging characters

Profile characters in easy steps and plan the goals and motivations that underlie suspense.

3. Keep raising the stakes

For narrative suspense and a sense of tension, your protagonist needs to try and fail a number of times. Or, if they succeed in reaching their goal at first try, adverse possible consequences need to lurk in the background. For example, Timmy might arrive at the party, having snuck out undetected, and notice his phone buzzing away with worried and/or angry texts. This small sign tells us he isn’t completely off the hook.

There are a number of ways to structure your novel to ensure that you have points of rising conflict throughout.

One way way of providing tension in writing is to keep the rule of threes in mind. The rule of threes simply states that there should be two unsuccessful attempts to solve a problem before the third successful one. When you brainstorm rising and falling plot points using the ‘Core Plot’ section of our outlining tool, try create two falling plot points (situations that take your character further from where they want to be) to one event where their situation improves.

This is less a hard-and-fast rule than a reminder that success is often hard-won. The interesting and exciting type of success, that is.

You could also consider using parallel plots to raise the tension stakes: you could present two characters in separate spaces, with the stories being told concurrently.

The key to how to build tension and suspense in a scene or story is to let it ebb and flow:

4. Allow tension to ebb and flow

You may be tempted to keep a constant stream of exciting things happening in order to ensure that the interest of your readers never flags. Yet this will in fact have the opposite effect.

Not only do you need quiet periods to build things like character, but if it’s all tension, all the time, your readers will simply get worn out.

It’s important to pace your suspense, and while the big moments may grow until you reach the climax at the end of the book, along the way, there should be smaller moments of tension and ease, too.

5. Keep making the reader ask questions

How do you keep readers engaged in the quieter moments of your story, when it isn’t all nail-biting action and hair’s-breadth escapes? One way is by creating good characters, who are interesting even when not in a state of emergency.

You also do so by ensuring that you are always raising interesting questions that your readers will want the answers to. Try to raise new questions at the ends of chapters in particular, so that you create a sense of forward propulsion to the next event (and the next).

One practical way of achieving this is through the use of varying sentence structure. When writing action and a fast-paced passage, use shorter sentences, ramp up the tension when something is happening. Have longer sentences when you are describing a room, for example, in a place where you are not wanting to increase the tension.

6. Create internal and external conflict

Tension is most interesting and varied when it arises both from forces outside of the character and those within. External conflict is conflict such as a fistfight between two adversaries, or a character’s fight for survival on a bitterly cold mountain pass (a ‘character versus environment’ conflict). Internal conflict refers to characters’ inner struggles. The difficult choices they grapple with, and the flaws, vulnerabilities or weaknesses that get in their way.

In some cases, the two types of tension may reflect one another; a character who struggles with a terror of public speaking may face an external conflict that brings that internal tension to the fore (for example, a sudden requirement that they give a major public talk).

7. Create secondary sources of tension

Often, we juggle multiple tensions and challenges at once. The protagonist of your romantic novel may not only be dealing with unrequited love but also with her dying parent or a challenge at work. Your FBI agent protagonist may be experiencing tension with her husband.

Think about your own life and the lives of everyone you know. Who has to juggle many balls in the air right now? What are the individual challenges? We all deal with conflict and tension from multiple sources, and your characters should be no different.

For example in Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn, the main tension revolves around the disappearance of Amy Dunne, but secondary sources of tension arise from the media frenzy and public scrutiny, as well as the complex dynamics within the Dunne marriage.

8. Make the story unfold in a shorter space of time

In a popular TV series like 24 or a tense thriller by Paula Hawkins or Gillian Flynn, characters are constrained by a time limit. A classic, Agatha Christie -like mystery novel set-up, in which a murder occurs at a country house over a weekend, is a good example of this.

This approach is not suitable for every story, but if you can narrow the story you are telling to a short time-frame, and keep events concrete, clear and fast-paced, requiring urgent resolution, this will aid tension.

Create a comprehensive outline of your story, including plot points that add tension, using Now Novel’s outlining dashboard.

22 replies on “How to create tension in a story: 8 simple steps”

Hey, I love this blog post! I am actually going to cite it for my English essay, can you tell me the publish date?

Hi Kaisa, thank you! It was first published on June 5th 2014. I hope your essay went well.

kaisa_clark 5++

ty for the artical . its verry helpfull

Hi Karen, thanks for reading our blog! Have a great week.

what was his strength??

We’ll never know 🙂

I like how this helps with writing.

Thank you, Kylie. We’re happy you found our article useful. Remember to subscribe to our newsletter to get notified when we have a new one.

Really helpful : > <3

I’m glad to hear that, Jasmine! Thank you for sharing feedback on our articles.

this was very helful thank you for posting this i will subscribe noow but i have a question how can characters add tension by movement?have a great day!

Hi James, thank you and thanks for reading. That’s a great question. Here are some ideas for creating tension through movement:

– Movement suggesting anxiety or worry, such as pacing up and down, frequently checking a window, lookout, or device.

– Increasing velocity (a car accelerating, a person breaking into a sprint).

– Sudden, fast movement that makes one say ‘What was that!?’ (for example I saw a large bird of prey flying into the tree-filled sprawling garden of a big house up my road the other day – the sudden movement gave me a fright, and it was so unexpected that I questioned what I’d seen but the owners came outside and said they’d seen it too).

I hope these ideas help!

Concisely put. My thanks. For me, the moral of the story is to plan how the story will evolve to reach its ultimate goal or climax. Build in adversarial conflicts, internal character challenges and environmental complications that rise and fall with increasing stakes toward the climax. Plan it out with each chapter having its own goal and resolution building forward. I like the use of movement, reflections, perception and gut feelings as tell-tale keys to create the over-all effect. Of course, it is a very dynamic process that is quite capable of generating unexpected tangents that can open memorable changes to the initial plan. I’m loving the ride. Thank you all for the guidance.

Hi Jamie, thank you for your feedback and for sharing your thoughts on tension. I like the way you put that, that it’s a ‘dynamic’ process that means one has to be open to unexpected tangents (which is why many authors prefer so-called ‘pantsing’ to plotting, I think). It’s a pleasure.

Woww so useful for my English exam!

Thank you so much, Now Novel!

Definitely recommend this site!

Thank you Arwa, I’m glad you found this article helpful. Good luck for your English exam!

thank you a lot! I’m sure that this post will help me in writing my narrative on the English exam.

It’s a pleasure, Yeva. Good luck with your English exam!

[…] is you feel like you have nothing to write about. But one of the best ways to cure this is to raise your story’s tension. In addition, extra tension will keep your characters working, your plot advancing, and your […]

[…] different shots to create a brief montage. Additionally, editors can jump between two scenes to add tension and suspense to a […]

[…] How to create tension in a story: 8 simple steps […]