‘Story exposition’ is often described as background, the necessary part to include so that readers know when, where and why your story takes place. Yet the exposition in a novel or short story is also an opportunity to entice, amuse, alarm and surprise your reader, foregrounding engaging themes and voices. Read on for a definition of exposition in fiction, plus examples taken from fantasy, historical fiction, speculative fiction and other genres:

Story exposition: Useful definitions

What is story exposition?

Oxford Reference gives multiple useful definitions of exposition in a story.

On one hand, story exposition explains the circumstances giving rise to the story’s main action. Exposition is:

The first phase in classical narrative structure, presenting circumstances preceding the action of the narrative.

Exposition also indicates the story’s genre (and thus what type of story to expect).

Oxford Reference uses the example of a dialogue about a case in a crime drama:

In drama, a kind of writing where characters talk about the plot: for example, in crime dramas this may take the form of a police briefing where officers are told about the case they have to solve.

This is called expository dialogue.

They further qualify, however, an important detail about story exposition: It can read as undramatic (or to put it another way, dry):

This kind of writing is sometimes necessary but is often undramatic: screenwriters, for example, are advised to avoid lengthy or explicit exposition.

So how do you make story exposition explain your world, your characters and starting scenario without the pitfall of it not being engaging (being ‘undramatic’)? First, a word on genre and story exposition:

What about genre-specific exposition?

As the second definition of exposition above (on its dramatic function) shows, genre will likely influence what you include in your book’s exposition.

In a fantasy novel, exposition might reveal the origin story or genesis of your magical world (as in Sir Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series or C.S. Lewis’ Narnia).

In romance, the exposition may show that the protagonist has fled to a tropical idyll to get over a disastrous relationship (as the setup for their plunging into a new relationship), for example.

Historical fiction often reveals the period or events we’re dealing with via an illustrative scene or action (such as evacuation order pamphlets raining down on a city during World War II in the short opening chapter in All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr).

If you are curious how to approach exposition for your genre, pick up a favorite novel in the same genre. Study the opening chapters, and ask:

- How does the author introduce or explain place, time and the core scenario?

- What significant details are introduced first?

- What details suggest context?

For example, evacuation pamphlets raining down is a powerful image explaining impending conflict in Doerr’s Pulitzer-winning novel mentioned above.

Exposition can be both direct and indirect.

Direct exposition is when you tell your reader exactly what is happening in a story, giving descriptive key details, for example: ‘He walked through the kitchen looking for his wife. The kitchen was filled with dirty dishes.’ Such background details help to show the reader what your character might be thinking and what choices they might make and introduce their world to you, giving your reader key background information.

Indirect exposition is when details are revealed through showing, such as in dialogue between characters revealing information; it’s also used to give readers clues though the narrative and the setting, allowing the reader to infer clues about the fictional world. Flashbacks fall into this label too.

Using effective narrative exposition means you can avoid the dreaded ‘info dump’. This is, for example when a writer crams in a whole lot of information that doesn’t feel natural, or interrupts the flow of the story. There are more graceful ways to present information to your readers. Effective expository writing means using a balance of many different elements.

Now let’s explore examples of exposition and 7 ways you can use it to reel readers in:

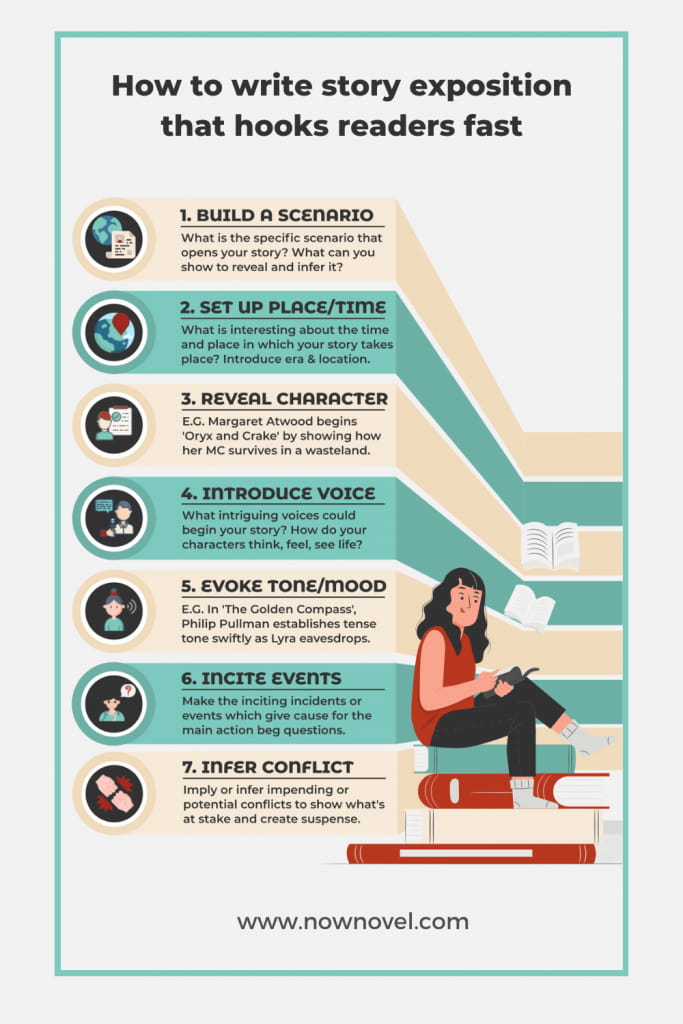

7 ways to write good story exposition

- Build a specific scenario

- Set up vivid place and time

- Reveal intriguing character details

- Introduce engaging voices

- Evoke precise tone and mood

- Create bold inciting incidents

- Introduce important conflict

Let’s explore some examples:

1. Build a specific scenario

Great story exposition often introduces us to a specific, intriguing scenario. Quickly, we get an idea of the initial, ‘who, what, why where and when’ of the story.

In the opening paragraph of One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel Garcia Marquez refers in passing to a main character facing an execution firing squad ‘many years later’.

This is a helpful reminder that the unique scenario you introduce at the start of your book doesn’t have to be from your character’s present. You could flash back to a significant memory, or tease a future story event (if the narrator is omniscient or non-involved, that is, and thus knows what will happen in the future).

Whatever point in a character’s life you choose to begin your story, exposition in narration (or dialogue) has similar functions:

- Introducing an interesting scenario (what has happened, is happening, or will happen)

- Introducing compelling characters and/or settings connected to this interesting scenario

Example: Teasing the scenario in Anil’s Ghost

Michael Ondaatje’s Anil’s Ghost follows the titular Anil, a forensic anthropologist sent by a human rights group to investigate political murders in Sri Lanka.

Ondaatje quickly introduces the scenario in expository narration which teases a forensics team’s arrival on site:

When the team reached the site at five-thirty in the morning, one or two family members would be waiting for them. And they would be present all day while Anil and the others worked, never leaving; they spelled each other so someone always stayed, as if to ensure that the evidence would not be lost again. The vigil for the dead, for these half-revealed forms.

Michael Ondaatje, Anil’s Ghost (2000), p. 5.

In a simple, short paragraph, Ondaatje’s exposition shows us:

- Details about the life of a forensic anthropologist (the early rising and long hours)

- A key character’s name (Anil) and her involvement in the scenario

- The nature of the action (that the team – whose work and its object is mysterious at this point in the story – is seeking evidence)

- Revealing visual details: the description of the dead as ‘half-revealed forms’ suggests the eerie sights of an archaeological dig

What initial action could suggest the specific scenario underway in your story?

2. Set up vivid place and time

Story exposition has many functions. Besides explaining circumstances where necessary, it also sets up place and time.

If your reader needs to know, for example, that your story unfolds in pre-modern England, how can you creatively expose or explain these specifics?

You could write, ‘Our story begins in early England’ (though this is quite on-the-nose or literal). See how Kazuo Ishiguro creates a sense of a folkloric, early era in The Buried Giant:

Example: Exposition of place and time in The Buried Giant

Ishiguro’s novel describes an early England after the Roman invasions. An elderly husband and wife, Axl and Beatrice, go on a quest to find their long lost son. He begins by describing the way Axl and Beatrice’s England differs from modern England:

You would have searched a long time for the sort of winding lane or tranquil meadow for which England later became celebrated. There were instead miles of desolate, uncultivated land; here and there rough-hewn paths over craggy hills or bleak moorland. Most of the roads left by the Romans would by then have become broken or overgrown, often fading into wilderness.

Kazuo Ishiguro, The Buried Giant (2015), p. 3

Ishiguro gives specific examples of the way this harsher, wilder landscape differs from the modern world. His focus on elements of danger and struggle sets a good tone of uncertainty for Axl and Beatrice’s impending journey:

Even on a strong horse, in good weather, you could have ridden for days without spotting any castle or monastery looming out of the greenery. Mostly you would have found communities like the one I have just described, and unless you had with you gifts of food or clothing, or were ferociously armed, you would not have been sure of welcome.

Ishiguro, The Buried Giant, p. 4

These details create a sense of the wild, unforgiving landscape that will make any travel seem like either a brave or foolhardy decision. They supply useful context for understanding the nature of living in/with the natural world in pre-modern times when nature held far more unknowns and mysteries for the average human.

3. Reveal intriguing character details

Story exposition supplies key character information fast, in contemporary novels and classics alike.

In the first pages of Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield, we learn about the circumstances of David’s birth (that his father died six months before he was born) quickly.

Nick Hornby begins Slam, his novel about a sixteen-year-old skateboarder, with the protagonist listing ‘good stuff’ that has happened over the past six months, such as ‘Mum got rid of Steve, her rubbish boyfriend.’

Introducing curious, intriguing details about characters early is one way to start explaining your world using showing rather than telling.

Example: Post-apocalyptic character exposition in Oryx and Crake

Margaret Atwood begins her speculative fiction novel Oryx and Crake (2003) thus:

Snowman wakes before dawn. He lies unmoving, listening to the tide coming in, wave after wave sloshing over the various barricades, wish-wash, wish-wash, the rhythm of a heartbeat. He would so like to believe he is still asleep.

Margaret Atwood, Oryx and Crake (2003), p. 3.

There are several reasons why this is good character-focused exposition:

- We’re told a pivotal character’s name, and it’s intriguing: ‘Snowman’ is not a typical human name. Because identity and memory later prove crucial themes, it makes sense Atwood introduces her character by his adopted, ‘post-human’ name

- We learn something about a character’s emotional life: Why would Snowman ‘so like to believe he is still asleep’? We guess there is something causing him displeasure or unhappiness

- There’s teasing information about the setting: Why are there barricades?

In one paragraph, Atwood’s exposition raises questions about names, the reasons underlying a character’s emotions, and their environment. It’s a good yet not extravagantly ‘showy’ hook.

Get feedback on your story

Join Now Novel to swap critique with likeminded writers and get weekly pro crits when you upgrade your membership.

LEARN MORE

4. Introduce engaging voices

Effective story exposition often introduces us to interesting, vivid voices.

One of the reasons Catcher in the Rye has often made lists of books to read in your lifetime is because the voice of Holden Caulfield is so utterly believable. We can feel Holden’s world-weary, cynical outlook in the narration that opens the story:

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it…

J.D. Salinger, Catcher in the Rye (1951), p. 3

The fact Holden ‘refuses’ us that David Copperfield type of story exposition tells us about his withdrawn, disaffected teenaged outlook.

Exposition of character is built in the gradual gathering of details: What your characters love, hate, desire, fear, love to talk about, let slip, refuse to say. You could say that in many of the greatest stories, character exposition never stops. We keep getting to know the character better.

Example: Attitude and outlook in A Little Life

Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life is full of intriguing characters whose personalities and attitudes are finely drawn.

Here, for example, we learn about the character JB (a painter who works in reception at a SoHo art magazine in the hope he’ll get a feature):

JB wore a perpetual expression of mild disbelief while at his job, both that he should be working at all and that no one had yet thought to recognize his special genius. He was not a good receptionist. Although the phones rang more or less constantly, he rarely picked them up; when any of them wanted to get through to him (the cell phone reception in the building was inconsistent), they had to follow a special code of ringing twice, hanging up, and then ringing again.

Hanya Yanagihara, A Little Life (2015), p. 7.

In Yanagihara’s rapid exposition of JB’s ambitions and his desires, we quickly begin to understand who JB is, and the steps he’s taken so far towards his goal.

5. Evoke precise tone and mood

One of the key purposes of exposition in a story is expectation-setting. What will the reader expect from the tone and mood of your story’s opening page alone?

If the tone is drily satirical, for example (like Terry Pratchett’s in the Discworld books), your reader will expect comedy.

A darker tone and mood will likewise established a more Gothic or eerie tone.

See, for example, the tense tone and mood Philip Pullman creates in the opening of the first book in the His Dark Materials trilogy. It sets good tone for the poisoning incident that follows:

Example: Tense expository tone in The Golden Compass

Lyra stopped beside the Master’s chair and flicked the biggest glass gently with a fingerail. The sound rang clearly through the Hall.

Philip Pullman, The Golden Compass (1995), p. 2.

“You’re not taking this seriously,” whispered her dæmon. “Behave yourself.”

Her dæmon’s name was Pantalaimon, and he was currently in the form of a moth, a dark brown one so as not to show up in the darkness of the Hall.

“They’re making too much noise to hear from the kitchen,” Lyra whispered back. “And the Steward doesn’t come in till the first bell. Stop fussing.”

6. Create bold inciting incidents

The inciting incident in a story (as we discussed here) sets the action in motion.

Your inciting incident is an excellent opportunity to not only get the action going but to reveal details about your world and in so doing, explain it to your reader.

The above example from the His Dark Materials trilogy, for example, is an effective inciting incident because it leaves us with burning questions about character motivation and identity. For example:

- Why is Lyra sneaking around?

- What is a ‘dæmon’? (It is obviously a shapeshifting companion of some kind)

When Lyra is interrupted in her sneaking and hides, eavesdropping, we quickly learn that this ‘Master’ figure is plotting a poisoning. It is a classic dark fantasy setup of a character being caught where they aren’t supposed to be.

Good story exposition often introduces characters’ goals and motivations. Take, for example, Eiji Miyake’s hunt for his estranged father in Tokyo at the start of David Mitchell’s novel number9dream:

Example: Clear goals in exposition in number9dream

It’s a simple matter. I know your name, and you knew mine, once upon a time: Eiji Miyake. Yes, that Eiji Miyake. We are both busy people, Ms Katō, so why not cut the small talk? I am in Tokyo to find my father.

David Mitchell, number9dream (2001), p. 2

7. Introduce important conflict

Exposition in a story explains not only the ‘why’ of your world or your characters’ lives, but also gives a sense of the ‘where to from here’.

The opening of The Golden Compass, for example, creates an immediate sense of danger in describing a world where people in powerful positions plot and poison.

Conflict in story exposition may be overt or implied (as it is – at least initially – in Anne Michaels’ Fugitive Pieces):

Example: Implied danger/conflict in Anne Michael’s Fugitive Pieces

In story exposition, you could write ‘Jakob Beer’s family have a hiding place for the children in case Hitler’s army arrives.’ Or you could leave the danger initially to subtle inference as Anne Michaels does:

My sister had long outgrown the hiding place. Bella was fifteen and even I admitted she was beautiful, with heavy brows and magnificent hair like black syrup, thick and luxurious, a muscle down her back. “A work of art,” our mother said, brushing it for her while Bella sat in a chair. I was still small enough to vanish behind the wallpaper in the cupboard, cramming my head sideways between choking plaster and beams, eyelashes scraping.

Anne Michaels, Fugitive Pieces (1997), p. 6

The reference to hiding places could easily be a child’s reference to ordinary games of hide and seek. It is only when Jakob’s family is attacked and killed in the pages that follow that the reader realizes that this hiding place serves a darker purpose.

Its passing mention thus foreshadows conflict as well as informing the reader of how it is that Jakob is able to escape.

The interweaving of loving description of Jakob’s family and the description of the hiding place only make the ensuing tragedy more heart-wrenching. This illustrates well how the best exposition often serves multiple informing and explaining purposes at the same time.

Want to start a novel with a strong central idea and a plan for finishing? Join Now Novel and brainstorm your best ideas.

13 replies on “How to write story exposition that hooks readers fast”

All of your examples are from the opening pages of books. Next time, can you give us examples from further on in a MS?

Happily, Maggie. Thank you for the suggestion and thanks for reading.

This was really useful, thank you

Thank you this was very helpful

It’s a pleasure, thank you for reading our articles.

[…] Structure, Plot is divided into five major parts: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action and resolution. A plot outline goes into detail about these […]

Me: a 7th grader trying to write a Detailed Book Report

This article: giving me all the info I need for technically the rest of my reports. Tysm!

?

I’m thrilled to hear that, Iris. I hope you get top marks for your book report. Good luck!

Me: A ninth grader trying to write a story about the Chicago race riots, and this basically helped me how to start writing an exposition.

That’s awesome to hear, Bella. I hope the story you’re writing is developing well and teaches readers important lessons around those tragic events. Thank you for reading our blog.

[…] How to Write Exposition that Hooks Readers – NowNovel.com […]

These articles are always so helpful. Like protein for my writing fitness.

I’m glad to hear that, Crawford. If you haven’t already, subscribe to our newsletter for bonus content and to be first to know whenever we publish.